Capitalism is a global system, and the struggle to overthrow it, therefore, has to be global. That explains why since the days of Marx and Engels, Marxists – revolutionary communists – have organised on an international level, from the First International, through to the Second, the Third, and the Fourth.

Today we are once again faced with a capitalist system in deep crisis globally. Everywhere we look we see wars, civil wars, famine, climate change, the rising cost of living, debt at unprecedented levels, and political crises in one country after another, with sharp changes and turns to the left and the right.

As a result we are seeing revolutionary outbursts of the masses all over the world, such as in Sri Lanka last year, and Kenya and Bangladesh this year. The world is tobogganing towards social revolution everywhere.

This poses once again, as in the days of Lenin, the need for an international organisation that gathers together the revolutionary communists of all countries. That is why we have launched the Revolutionary Communist International (RCI) as a beacon to all serious workers and youth who have understood the need for revolution.

Our objective is to build a mass revolutionary international that can provide the leadership that is required to guarantee that the coming wave of revolution will be successful in putting an end to the capitalist system once and for all, and that it will not end in defeat for the working class, as it has done in the past.

The early years of the Third (Communist) International, known as the ‘Comintern’, are a precious historical experience for us today as we proceed to build the sections of the RCI. How will the relatively small forces that we have today be transformed into powerful mass Revolutionary Communist Parties?

The need for a new international

The outbreak of the First World War in July 1914 was a decisive turning point in world history. The imperialist powers of Europe mobilised their respective working classes to slaughter one another in pursuit of their predatory war aims. Then, more than ever, a clear internationalist leadership was needed, to cut across the war fever and help turn the imperialist war into a class war. But nearly all the leaders of the parties of the Second International buckled under pressure, and gave support to ‘their’ respective capitalists.

The seeds of this betrayal were to be found in the fact that the Second International, founded in 1889, developed during a period of capitalist upswing. The ability of the working class in this period to win reforms through the class struggle impacted the outlook of its leaders, who developed the view that socialism could be achieved through gradual reform. Thus, over time, the programme of socialist revolution was substituted for class collaboration and reformism.

Although a number of polemics were waged against these opportunist trends, the degree of degeneration took place largely below the surface. In everyday activities many of its local representatives had begun to behave in a de facto class-collaborationist manner. However, the official position of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) remained one of adherence to Marxism. Hence Lenin was so shocked to read about the capitulation of the SPD’s leaders at the outbreak of the war, that he thought the issue of their paper announcing their support for the war was a forgery of the German general staff.

Once the scale of the betrayal became clear to Lenin, however, he correctly diagnosed that the Second International was dead for the purpose of leading the world socialist revolution to victory. He therefore proclaimed the need for a third international as soon as November 1914.

But given the circumstances of the imperialist war, with the emptying of workers’ organisations, combined with the betrayal of the ‘socialist’ leaders, the conditions to found such an international did not yet exist. In fact, at the anti-war Zimmerwald conference in 1915, Lenin remarked that the genuine internationalists of the world could be squeezed into just a few stagecoaches. It would take the development of events, chief among them the Russian Revolution of 1917, to bring the forces for a new international into being.

The importance of theory

Lenin’s most important task in refounding a revolutionary international was therefore to rescue the method and programme of genuine Marxism from the distortions of the opportunists.

It is not by chance that in 1914, after the First World War had broken out, Lenin took the time to study Hegel thoroughly. Why did he do this? It was because without an understanding of Hegel’s dialectics it is not possible to fully understand Marx’s method.

Lenin skilfully applied this method to combat the so-called ‘Marxists’ who were misquoting snippets of Marx to justify supporting ‘their own’ ruling classes during the war. Lenin’s writings during this period are therefore a treasure-trove of Marxist theory. They include The Collapse of the Second International (1915); his pamphlet Socialism and War (1915); and his famous Imperialism: the Highest Stage of Capitalism (written in January-June 1916).

Lenin’s clarification and defence of Marxism was vital to the Bolsheviks’ ability to lead the Russian Revolution to victory. This is evident in his Letters from Afar (written in March 1917); followed by his April Theses; and his landmark work, The State and Revolution (written in August-September 1917); all of which were essential in combating the vacillations of Bolshevik leadership during the course of the revolution.

The history of the Bolshevik Party is rich in lessons on how to build a revolutionary party. It went through periods of clandestine work, of small cells working in extremely difficult conditions, but also periods of mass work, such as in 1905 when the first Russian revolution broke out.

This rich experience of the Bolshevik Party would form the theoretical bedrock of the Communist International in the period of its first four congresses, 1919-22. This all emerges very clearly from the debates.

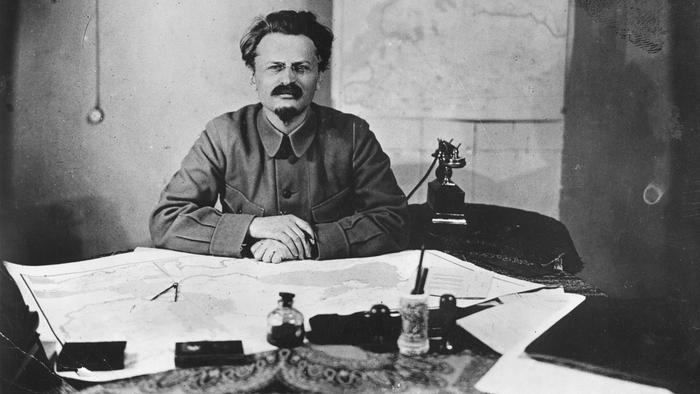

If one looks through the resolutions, documents and speeches of the first four congresses, the fundamental educational role of Lenin and Trotsky – two giants of Marxist theory – transpires clearly. They understood their task as to transmit their accumulated experience and ideas to a new generation of revolutionary leaders that were coming to the fore. In this way they could help arm the newly developing Communist Parties worldwide with the correct methods and tactics for victory.

The First Congress – a call to arms

Big events prepare the conditions for revolution, and in turn it is the crisis of capitalism that prepares those events. The Russian Revolution of 1917 inaugurated a period immediately after the First World War that saw a wave of revolution sweeping across Europe. The objective conditions for revolution had matured, or were maturing, in one country after another.

In January 1918 a general strike gripped Austria-Hungary that had revolutionary dimensions. And in November of that year, the German Revolution began, overthrowing the kaiser and bringing an end to the war. The SPD leaders were thrust into government, and did everything possible to hand power back to the capitalists. The revolution then returned to Austria, where the Austrian Social Democrats likewise betrayed the workers.

Meanwhile, the Second International had split into broadly three camps. First was the outright chauvinists, which had openly betrayed during the course of the war. Second was what Lenin called the ‘Centre’ – with Karl Kautsky as their figurehead – who disguised their opportunism with revolutionary language. And third was the growing revolutionary wing, many of whom split from the Second International to form Communist Parties in their respective countries.

The First Congress of the Comintern was held in Moscow between 2 and 6 March 1919 with the aim of fusing together the various revolutionary currents internationally. Only 52 delegates attended, given the difficulties travelling to Moscow during the height of the Civil War, combined with the fact that the process of radicalisation was still at an early stage. As such, the congress was more of a call to arms, to be a reference point for this developing revolutionary left wing internationally as the process of world revolution matured.

The congress issued a manifesto – drafted by Leon Trotsky – which boldly stated,

“It is the proletariat which must establish real order, the order of communism. It must end the domination of capital, make war impossible, wipe out state boundaries, transform the whole world into one cooperative commonwealth, and bring about real human brotherhood and freedom.”

One of the main aims of the congress was to draw a clear dividing line between itself and the reformists of the Second International, including Kautsky’s ‘Centre’. As such, much of the discussions focused on the recognition of the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ and soviet democracy – i.e. workers’ power – to which the reformists were hostile.

The congress therefore firmly raised the banner of world revolution for the workers of the world to see. The new Communist International would go on to become a reference point for millions in the stormy period of struggle that followed.

Rapid radicalisation

The class struggle builds up over decades, but there are periods in which we see rapid developments in the consciousness of the working class. In Britain, the number of days lost through strike activity were 35 million in 1919, and 86 million in 1921. Trade union membership went from 4.1 million in 1914 to 8.3 million in 1920. This was combined with a surge in support for the Labour Party.

In Germany the number of strikes in 1919 were 3,682, growing to 4,348 by 1922. Membership of the Socialist trade unions went from 1.8 million in 1918 to 5.5 million in 1919 – a surge of nearly 4 million workers in just one year. By 1920 membership of all the unions – not just the Socialist – reached 10 million. This is a statistical expression of the revolution that began in 1918.

In Italy the CGL – the Socialist-led trade union confederation – went from 250,000 members in 1918 to 2.1 million in 1920. Meanwhile the Italian Socialist Party’s (PSI) membership more than tripled in the same period, going from 60,000 in 1918 to 210,000 by 1920. These two years saw a massive strike wave, culminating in the occupation of the factories in September 1920.

Similar figures can be found for many other countries. Suffice it to say that everywhere the trade unions were expanding exponentially, and the parties of the working class were also significantly increasing their forces.

At the same time, everywhere we saw the trade union leaders playing a conservative role, holding back the workers, while open betrayal on the part of the political leaders of the working class was also taking place.

It was this experience that saw the emergence of strong left currents within the Socialist Parties. It was from these currents that some of the main Communist Parties in Europe would emerge, in countries such as Germany, France and Italy.

There is no one-fits-all formula here for how this process developed. In France, Italy and Germany the mass forces for the Communist Parties came from within the old Social Democracy.

In other places such as Britain, there was the fusion of small revolutionary groups into national sections of the Communist International. Elsewhere, across much of Asia, Africa and Latin America, the Communist Parties were built from a handful of initial cadres, China being the prime example.

France

The ranks of the French Socialist Party (French Section of the Workers’ International – SFIO) felt the impact of both the crisis in France and the Russian Revolution. In 1920 the party held two congresses: one in April, which nominated a delegation to visit Soviet Russia, and then a second in Tours, which was organised at the end of December of the same year.

The general secretary of the SFIO, Ludovic-Oscar Frossard, together with Marcel Cachin, the new editor of the party paper, L‘Humanité, called for unconditional membership of the Communist International. In opposition to this was the right-wing faction, led by the prominent deputy Léon Blum, while a third position, expressed by Jean Longuet, was for joining but with ‘certain conditions’, i.e. without fully adhering to the programme and principles of the Communist International.

After listening to the different positions expressed in the congress, a majority of the delegates, 3,252 against 1,022, voted to adhere to the Communist International. The party’s youth wing had already taken the decision to join the Communist Youth International some months previously.

A few months later they adopted the name of the Communist Party-French Section of the Communist International (PC-SFIC), with 110,000 members. Léon Blum split away to reform the SFIO with only 40,000 members.

Italy

In Italy, the PSI formally joined the Communist International in March 1919. At its congress in October 1919 held in Bologna it even called for the setting up of soviets in Italy and the overthrow of bourgeois democracy. But this was in words only; in practice it did nothing concrete to act consistently on these decisions.

The Bologna congress merely expressed the real wishes of the ranks of the party, but these were filtered through the reformist and centrist leaders.

In September 1920 the treacherous role of the reformists during the occupation of the factories accelerated the process of internal differentiation – between the genuinely revolutionary wing of the party, and the vacillating centrists and reformists.

When the party gathered for its congress in Livorno on 15 January 1921, the ‘Terms of Admission into the Communist International’ or the ‘21 Conditions’ as they are often referred to – adopted by the Second Congress of the Comintern to draw a line of demarcation against the opportunists – were at the heart of the debate. This explicitly posed the question of expelling the reformist wing of the party and its leaders, particularly Filippo Turati and Guiseppe Modigliani.

Amadeo Bordiga – who would become the leader of the Communist Party – argued in favour of accepting the 21 Conditions in their entirety. Giacinto Serrati, leader of the majority centrist current of the party, refused to accept this.

Three resolutions were presented to the congress, with Serrati winning the support of 100,000 members of the party, the right wing 15,000, and the communists 58,000.

The communists subsequently abandoned the congress, singing the Internationale, and gathered in the Teatro San Marco to found the Partito Comunista d’Italia (PCd’I), the Italian section of the Communist International.

Germany

In Germany the process was not as straightforward as in France and Italy. Nonetheless, it expressed a similar line of development: the bulk of the members of the future Communist Party of Germany (KPD), came from the mass ranks of the old SPD, which had grown massively on the back of the revolutionary events in the immediate period at the end of the war.

Initially, the genuine revolutionaries gathered around the Internationale Group, later to become known as the ‘Spartacists’, within the SPD. In April 1917 a major split occurred, with the formation of the ‘Independents’, the USPD. The Spartacists followed the split, but after the eruption of the German Revolution in November 1918, they decided to break with the USPD and founded the Communist Party at the end of 1918.

Largely in a reaction against the reformism of the SPD, and the opportunism of Kautsky and the majority of the USPD leaders, the KPD was born infected with ultra-left ideas. For example, they boycotted the trade unions and refused to take part in the election for the Constituent Assembly, called for January 1919. They were also prone to adventurism, such as the premature ‘Spartacist uprising’ in January 1919. After its two foremost leaders – Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht – were killed in the aftermath of the uprising, there were fewer experienced leaders capable of checking its ultra-left tendencies.

The USPD – the ‘Independent SPD’ – emerged as a major force, with 300,000 members in March 1919, rapidly growing to 800,000 by April 1920.

The Independents became a channel for the massive radicalisation of the working class. As a result, the majority of the USPD accepted the 21 Conditions and voted in favour of adhering to the Communist International at its October 1920 congress, and fused with the KPD. In the process, it split down the middle, losing its right wing. This was how the biggest Communist Party outside Soviet Russia was formed, with its 500,000 members.

Britain

In France, Italy and Germany we have concrete examples of mass Communist Parties emerging from the left wing of the old Social Democracy. In Britain, however, the party was formed in 1920 through the merger of a number of smaller Marxist groups, which included the British Socialist Party, the Communist Unity Group of the Socialist Labour Party, as well as the South Wales Socialist Society. One year later the Scottish Communist Labour Party also joined.

As in Germany and Italy, however, the party was initially infected with ultra-left tendencies. Some were of the opinion that parliamentary work should be rejected, and that the party should have nothing to do with the Labour Party.

However, there was no avoiding the question that the mass of workers in Britain still saw the Labour Party as their point of reference. That is why Lenin dedicated a section of his text, ‘Left-wing’ Communism: An Infantile Disorder, to educate and reorient the British Communists to work in and around the Labour Party. And an entire session of the Second Congress of the Communist International was given to debating this question in detail.

The Second Congress

The developing radicalisation of a layer of the working class worldwide was reflected in the composition and tasks of the Second Congress of the Comintern, held between 19 July – 7 August 1920. Whereas the First Congress was more of a rallying call to small communist trends and groups, the Second Congress saw 218 delegates from 54 parties and organisations worldwide attend to clarify the programme and tactics of the new International.

Since a large layer of the ranks of many of the Socialist Parties were keen to join the Comintern, there was a danger that many of the old reformist leaders and party functionaries could jump ship with them, in order to try and preserve their relevance and positions.

For example, the Italian Socialist Party, the PSI, had joined the Communist International en bloc under the pressure of the rank and file of the party that had been revolutionised by the intense class struggle of the period 1918-20 in Italy. However, the reformist wing, headed by Turati and Modigliani, were still in the party, working against the revolutionary ideas of the International.

This danger was brought to the attention of the Second Congress from the outset. A series of discussions were held, including on the role of Communist Parties, soviets, and methods of work, in order to firmly distinguish the Communists’ programme from that of the reformists. These were summed up in the 21 Conditions, drafted by Lenin himself:

“Parties and groups only recently affiliated to the Second International are more and more frequently applying for membership in the Third International, though they have not become really Communist. The Second International has definitely been smashed. Aware that the Second International is beyond hope, the intermediate parties and groups of the ‘Centre’ are trying to lean on the Communist International, which is steadily gaining in strength. At the same time, however, they hope to retain a degree of ‘autonomy’ that will enable them to pursue their previous opportunist or ‘Centrist’ policies. The Communist International is, to a certain extent, becoming the vogue.

“The desire of certain leading ‘Centre’ groups to join the Third International provides oblique confirmation that it has won the sympathy of the vast majority of class conscious workers throughout the world, and is becoming a more powerful force with each day.

“In certain circumstances, the Communist International may be faced with the danger of dilution by the influx of wavering and irresolute groups that have not as yet broken with their Second International ideology.” (Emphasis added.)

In order to protect the new International from such contagion, point 7 specifically stated that it “cannot tolerate a situation in which avowed reformists, such as Turati, Modigliani and others, are entitled to consider themselves members of the Third International”. This was a measure aimed specifically at incorrigible class traitors, at the openly reformist class collaborators who had become members of some of the sections of the Communist International.

Programme and methods

It was the Second Congress which saw in-depth debates on a series of important questions.

For example, Lenin warned against the idea of the ‘imminent collapse of capitalism’ as an ultra-left error that needed correcting. He warned the delegates at the congress that although a revolutionary crisis was clearly present in many countries, there was still the possibility for the capitalists to find a way out, as long as they succeeded in holding on to power, and the outcome depended on the revolutionary party in each country. There was no preordained guarantee of successful revolution.

Lenin also dedicated much attention to other key questions of theory. He wrote (and amended) the Draft Theses on the National Question and Colonial Questions for the Second Congress. The Theses represented a clear break with the often ambiguous positions adopted by parties of the Second International, where the right-wing reformists saw in colonialism a ‘European civilising mission’, thereby supporting their own national bourgeoisies’ imperialist ambitions.

The Communist International stood firmly on the side of the oppressed peoples in the colonies and called on the working classes of the advanced countries to support the anti-imperialist struggles of these peoples. It distinguished clearly between oppressed and oppressor nations. Without such a principled stand on colonialism it would have been impossible to build sections of the International in the colonial countries. Again, we see how ideas are the key to building an organisation.

For example in China – at that time a semi-colonial country – these ideas had a profound impact in bringing together the founding forces of the Communist Party. Its initial cadres started as a Marxist study group at Beijing University, with a professor – Chen Duxiu – playing a key role.

At first the group was made up of intellectuals, who then went on to found the Communist Party of China in July 1921. Twelve delegates gathered at its founding congress, representing 59 members in total.

The extremely small forces they had did not hold them back from calling themselves a party, which was literally built from scratch. This small initial grouping was able to reach the figure of 1,000 members – mostly university students and intellectuals – by May 1925.

Then came a major historical event, the Chinese Revolution of 1925-27 which opened huge possibilities for the party, as tens of thousands of workers swelled its ranks. In two years the party membership ballooned to close to 60,000.

The Russian Revolution had a huge impact globally. Communist Parties and groups began to emerge in many other countries around the world, for example in the Middle East or in Latin America, where often they started as small circles of intellectuals, which later began to connect with wider layers of workers.

Against ultra-leftism

The Communist International had succeeded in attracting a large layer of militant workers and youth to its banner, many of whom had been radicalised by recent events. However, many of them – including the leaders of the new Communist Parties – were completely inexperienced when it came to an understanding of the Marxist method and tactics.

Many of these new communists had a healthy rejection of the opportunism of the Second International, which had adapted itself to parliamentarianism. Likewise, many were frustrated by the reformist leaders of the trade unions, who acted as a brake on the movement. A layer, however, drew the false conclusion that ‘Bolshevism’ meant simply revolutionary intransigence and a rejection of all compromises. They thought that it was sufficient to build Communist Parties by simply denouncing bourgeois democracy and setting up purely ‘revolutionary’ trade unions. Herman Gorter, a Dutch Communist, even attacked Lenin, accusing him of ‘opportunism’ for advocating parliamentary work and work in the trade unions.

Lenin described this attitude as ‘ultra-left’, or ‘left-wing communism’. He stressed that it is not sufficient to simply denounce capitalism and wait for the masses to join the revolutionary party. One has to win the masses – which requires the utmost flexibility of tactics. This was the key lesson from the entire history of the Bolshevik Party.

Lenin understood that unless such sectarian ideas were rapidly corrected, the sections of the Communist International could be destroyed on the rocks of revolution itself. Nevertheless, Lenin described this mistake as ‘infantile’, i.e. a product of immaturity, which could be corrected through patient explanation and discussion.

Lenin therefore wrote his ‘Left-Wing’ Communism: An Infantile Disorder in April-May of 1920 precisely to tackle this question at the Second Congress of the Comintern. In it he sums up the lessons the Bolshevik Party had learned from its participation in three revolutions between 1905 and 1917, and the lessons learned since conquering power. He warns against both the dangers of opportunism and ultra-leftism.

It was published in German, English and French, so that all the delegates to the Second Congress would be able to read it. The importance Lenin gave to this text can be seen from his personal involvement in the book’s type-setting and printing. He wanted to make absolutely sure that it would be published before the opening of the congress.

Both Lenin and Trotsky sought to clarify genuine communist ideas and tactics through patient explanation and debate in and around the congresses of the Communist International. They wrote lengthy texts and gave speeches on the key questions.

As we can see from this example, Lenin, in most cases, sought to solve political problems with political methods, not organisational measures.

Lenin dedicated much time to this. He understood that you cannot convince and educate genuine, thinking, revolutionary communists by using commandist methods. All you achieve with that is ‘obedient fools’ who are incapable of orienting themselves in the storm and stress of the class struggle and revolution.

The trade unions

The Second and Third Congresses also discussed at length the trade union question. In the ‘Theses on the Trade Union Movement, Factory Committees and the Third International’, discussed at the Second Congress, it is stated clearly that:

“… the trade unions proved to be in most cases, during the war, a part of the military apparatus of the bourgeoisie, helping the latter to exploit the working class as much as possible in a more energetic struggle for profits. Containing chiefly the skilled workmen, better paid, limited by their craft narrowmindedness, fettered by a bureaucratic apparatus disconnected from the masses, demoralised by their opportunist leaders, the unions betrayed not only the cause of the social revolution, but even also the struggle for the improvement of the conditions of life of the workmen organised by them.”

Having stated this very bluntly and clearly, the very same Theses also acknowledged that,

“… the wider masses of workers, who until now have stood apart from the labour unions, are now flowing into their ranks in a powerful stream. In all capitalist countries a tremendous increase of the trade unions is to be noticed, which now become organisations of the chief masses of the proletariat, not only of its advanced elements. Flowing into the unions, these masses strive to make them their weapons of battle.

“The sharpening of class antagonisms compels the trade unions to lead strikes, which flow in a broad wave over the entire capitalist world, constantly interrupting the process of capitalist production and exchange. Increasing their demands in proportion to the rising prices and their own exhaustion, the working classes undermine the bases of all capitalist calculations and the elementary premise of every well-organised economic management. The unions, which during the war had been organs of compulsion over the working masses, become in this way organs for the annihilation of capitalism.” (Emphasis added.)

Here we see the dialectical method of Lenin at work. It allows communists to see how things, as they develop and change, can actually turn into their opposite. The trade unions were being pressurised from two totally opposed class interests.

On the one hand the capitalists worked consciously to corrupt the trade union leaders in order to use them to police the working class. While on the other hand the ranks of the unions were growing as the mass of workers, feeling the pressure of inflation and worsening working conditions, pushed the leaders into taking a stand in their interests.

That is why the Theses stated that “the Communists must join such unions in all countries”, and that all attempts to withdraw from the unions, or to organise alternative unions, represented “a great danger to the Communist movement.” To do so threatened “to hand over the most advanced, the most conscious workers to the opportunist leaders, playing into the hands of the bourgeoisie”.

As in all such statements, there is always the danger of a mechanical one-sided interpretation. Did the principle that communists should join the unions exclude always and everywhere the possibility of splitting away from them?

Lenin’s method was a flexible one, which always took into account the concrete conditions the communists were facing. That is why the very same document just a few paragraphs later states, “the Communists ought not to hesitate before a split in such organisations, if a refusal to split would mean abandoning revolutionary work in the trade unions”, while at the same time:

“The Communists, in case a necessity for a split arises, must continuously and attentively discuss the question as to whether such a split might not lead to their isolation from the working masses.”

The Third Congress also discussed the Theses on Methods and Forms of Work of the Communist Parties Among Women which outlined the special measures to be taken by the Communist Parties to develop their work among women.

The congress also highlighted the greater radicalisation that was taking place among the youth and promoted the Communist Youth International as an integral part of the Communist International, and under the discipline of its leadership, not as a separate entity.

Crises and consciousness

The congresses of the Communist International debated the ups and downs of the class struggle internationally. An important question that was discussed was the relationship between the economic cycle and the class struggle.

A simplistic and mechanical interpretation of this relationship can lead to the conclusion that an economic downturn always leads to an upturn in the class struggle, whereas an upturn in the economy produces stability in the system. The leaders of the International warned the national sections against this, and tried to transmit their theoretical understanding to the leaders and the ranks of the Communist Parties, as serious mistakes of evaluation could flow from such a conclusion.

This became especially important at the Third Congress of the Comintern, held on 22 June – 12 July 1921. The immediate postwar years had seen a crisis of capitalism, combined with a revolutionary wave across Europe. But by 1921 the system had succeeded in stabilising itself, due to the betrayals of the reformists. The upturn in the economy disoriented a number of communist leaders, who took a mechanical approach to the dynamics of the class struggle.

In his ‘Report on the World Economic Crisis and the New Tasks of the Communist International’, Trotsky explained:

“It would […] be very one-sided and utterly false [that] a crisis invariably engenders revolutionary action while a boom, on the contrary, pacifies the working class.”

Trotsky based his report on the experience of the class struggle in the early years of the 20th century in Russia, with its ups and downs. And in answering oversimplifications, he stated:

“Many comrades say that if an improvement takes place in this epoch it would be fatal for our revolution. No, under no circumstances. In general, there is no automatic dependence of the proletarian revolutionary movement upon a crisis. There is only a dialectical interaction.” (Emphasis added.)

Trotsky pointed out that there are moments in the class struggle when a severe downturn in the economy can actually dampen the combativity of the class. Only when the economy begins to recover do the workers feel stronger in relation to the bosses, and therefore – seemingly paradoxically – the working class can embark on militant struggle. The impact of an economic downturn or upturn on the class struggle is not immediate or mechanical. It can be delayed, but it also depends on the context, and on what has come before.

Trotsky concluded that whilst the capitalists were striving to reach a new economic equilibrium, the attempts to do so would eventually disrupt the social and political equilibrium. The ebb in the class struggle would inevitably give way at some point to a return of the world revolution. The task of the Comintern was therefore to prepare for the next wave by building powerful Communist Parties, with tactics capable of winning the masses.

The ‘theory of the offensive’

This discussion was especially important in the context of the ‘March action’ of the German Communists earlier that year.

Germany had been going through waves of revolution and counter-revolution since 1918. By this point, the KPD was the largest Communist Party outside of Russia, with over 500,000 members.

In March 1921, however, despite the revolution ebbing, the leadership of the KPD attempted to artificially provoke a new wave of revolution through the actions of the party alone. Some even went as far as blowing up a workers’ cooperative society headquarters and blaming it on the police.

The action followed the so-called ‘theory of the offensive’. A layer of ultra-lefts argued that Communist Parties should pursue ‘offensive tactics’ – regardless of the objective situation – in order to provoke workers into revolution.

No consideration was given to the real movement of the working class, and therefore the ‘action’ ended up as a complete debacle. Thousands were arrested, the KPD was outlawed, and more than 200,000 members either resigned or dropped out of activity.

Nevertheless, a layer of ultra-lefts within the KPD defended their tactics as correct. They were joined by leading figures in the Comintern such as Radek, Bukharin and Zinoviev, who welcomed the ‘theory of the offensive’. ‘Left Communists’ in Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Italy, Austria and France all praised the ‘March action’, and saw it as a heroic example to follow.

It therefore fell to Lenin and Trotsky to correct this ultra-left deviation at the Third Congress of the Comintern. They explained that courage and heroism of communists by itself is insufficient to lead a revolution. For this, it is necessary to win over the masses.

In order to do this, the Communist Parties required leaders who were able to analyse the objective situation, and determine which stage of the revolutionary process they were passing through. Hence the importance of a dialectical understanding of the class struggle, and an ability to read the consciousness of the masses at a given stage.

Revolutionary situations cannot be created at will. Instead of attempting to command the working class into action, Communist Parties had to know how to genuinely dialogue with the masses. This meant an ability to connect with them at their existing level of consciousness, and raise it to an understanding of the need to take power. But only when a revolutionary situation had fully matured and the communists had won over a majority of the working class, would it be possible to lead a successful insurrection.

Summing up the discussion, Trotsky remarked that “only a simpleton would reduce all of revolutionary strategy to an offensive”. The art of leadership involves not just directing forces to advance, but also knowing when to retreat. This can mean the difference between an orderly retreat – preserving your forces for future battles – and a complete rout.

In the end, the position of Lenin and Trotsky was accepted at the congress, the watchword of which became: ‘To the masses!’.

The united front

What leaders such as Lenin and Trotsky were trying to do was to raise the level of understanding of the ranks of the Communist International, starting with the national leaders of the sections. One important question they tried to inculcate into them was the question of how the revolutionary party, which has conquered the advanced layers – the vanguard of the working class – can win the masses who are still influenced by the reformist leaders in the movement.

When major historic events unfold, large layers of the masses begin to enter the arena of struggle. In the process, they begin to put to the test their own leaders. Trade union leaders who refuse to fight, who use their positions to hold back the workers, will eventually be pushed to one side and be replaced by bolder leaders. On the political front, workers seek leaders who have answers to the crisis of the system, or at least seem to have the answers – leaders who are prepared to lead the fight against the system.

There is, however, no ‘big-bang’ moment in the development of revolutionary consciousness. It is not one single event, but a series of events unfolding over an unstable period, with its ups and downs, with outbursts of intense class struggle followed by periods of retreat, that eventually produces leaps in consciousness.

Different layers of the working class also move at different tempos. There are advanced layers that begin drawing conclusions ahead of the rest of the class. This is the layer that must be won to the revolutionary party, organised, educated, and oriented to the mass of the working class.

We have to exclude the idea that the revolutionary party can win the masses in periods of prolonged upswing for the capitalist system, i.e. when the system can grant concessions to the working class. In such times reformism dominates, as was the case in the latter part of the 19th century and early years of the 20th century. If it seems that capitalism can deliver the goods, why the need to overthrow it?

In such periods the genuine Marxists are reduced to small numbers going against the stream, holding together their forces, preserving the ideas of revolutionary Marxism. Even when the system starts to enter into crisis after such a lengthy period, the tendency initially is to look back to the ‘good old days’ and seek ways of returning to them, rather than looking forward to the inevitability of revolution. Human consciousness tends to be conservative and it takes time for it to catch up with objective reality.

All this explains why in the early stages, the revolutionary wing of the movement is a minority, while the bulk of the working class seeks what appear to be more ‘realistic’ easier roads. And why initially, it is the reformist leaders who have greater sway over the masses.

That is why the Fourth Congress, held between 5 November and 5 December 1922, was called on to adopt the Theses On The United Front, which noted a “certain revival of reformist illusions” and “a spontaneous striving towards unity” within the working class.[11] Something very important had changed in the objective situation. As noted at the previous congress, the wave of revolution was receding, and a temporary stabilisation of the system was taking place. The Theses noted that:

“…as confidence steadily grows in those who are most uncompromising and militant, in the Communist elements of the working class, the working masses as a whole are experiencing an unprecedented longing for unity. The new layers of politically inexperienced workers just coming into activity long to achieve the unification of all the workers’ parties and even of all the workers’ organisations in general, hoping in this way to strengthen opposition to the capitalist offensive.”

In this context, the reformist parties such as the Labour Party in Britain, the SPD in Germany and the PSI in Italy still held sway over wide layers of the working class. The question was posed, therefore, as how to win these layers to the ideas of revolutionary communism? This could not be done with sectarian posturing and denunciation. It required great skill in applying the tactic of the workers’ united front.

The basic concept was that to win the confidence of the ranks of the reformist organisations and the trade unions, it was necessary for the Communists to show their readiness to struggle in a united front of the working class. This would fight for the immediate interests of the working class, while placing demands on the reformist leaders and raising the more general interests of the class as a whole.

In the day-to-day struggles it would therefore be possible to show in practice who the consistent fighters were, put to the test the class-collaborationist leaders, and thus win over the ranks to the revolutionary programme of the Communists – to the programme of socialist revolution.

The way the united front tactic was applied varied from country to country, depending on the local conditions, and the strengths and weaknesses of the individual Communist Parties relative to the mass reformist organisations. But the essential idea remained the same.

In Italy it translated into the concrete need to build the resistance to the growing danger of reaction. In October 1922 Mussolini was appointed Prime Minister by the king. Thus a united front would involve the PCd’I offering united action to the Socialist Party and the trade unions to counter the rising fascist violence.

In Britain, due to the relatively small forces of the Communist Party of Great Britain, the Theses stated:

“The British Communists must launch a vigorous campaign for their admittance to the Labour Party. […] The British Communists must do their utmost, whatever the cost, to extend their influence to the rank and file of the working masses, using the slogan of a united revolutionary front against the capitalists.”

However, in order for the tactic to be successful it required that “the actual Communist Parties carrying it out must be strong, united, and under an ideologically clear leadership.” Achieving this was the central task that Lenin and Trotsky posed themselves during the congresses of the International.

Unfortunately, they did not always succeed in this. The quality, the political level and understanding, of many of the leaders of the young Communist Parties, was not up to the tasks of the moment.

In the case of the leadership of the Italian Communist Party, figures such as Bordiga never accepted the advice of Lenin and Trotsky. In so doing, he contributed to a tragic division of the forces of the Italian working class precisely as the bourgeoisie was on the counter-offensive. The ruling class was intent on destroying the Italian labour movement completely, atomising it, killing thousands of its key local leaders, arresting many others, and finally establishing the crude dictatorship of capital in its most brutal form, fascism.

The importance of leadership

Looking back at that period, what emerges clearly is that what permits small revolutionary forces to rapidly transform into mass revolutionary parties are the rapid changes in the objective situation. The breakout of the First World War and the severe economic crisis that ensued, with mass unemployment and high levels of inflation, prepared the ground for revolutionary events.

However, without a fully worked out revolutionary theory, the potential for the building of mass revolutionary parties can also be lost.

The early years of the Communist International also underline the importance of building the cadres of the future revolutionary party long before the revolutionary events unfold, and demonstrate the importance of leadership within the revolutionary party itself. This was evident immediately after the outbreak of the February 1917 revolution in Russia, when the pressures of reformism were immense.

As we have stated, the mass of the working class in the initial stages of revolution seek out what seems to be the more practical, the apparently easier, road of reformism. That explains why in early 1917 it was the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries who dominated the movement. This had an effect on the leaders of the Bolshevik Party inside Russia, such as Kamenev and Stalin, who were bending under the pressure and leaning towards compromise and support for the provisional government.

It took a leader of the calibre of Lenin – a thoroughly educated Marxist, who understood the method of Marxism, which involved the application of dialectical thinking – to steer the party in the right direction, to hold it firmly to a revolutionary position, even when this meant going against the stream.

Thus, it was the dialectician Lenin who was able to resist the pressures after February 1917 and maintain a firm position. He could see further ahead than the local Bolshevik leaders. He could see the inevitable betrayal that would be perpetrated by the Menshevik leaders and how this would mean they would inevitably begin to lose the support of the working masses, and these would then be more open to the revolutionary position of the Bolsheviks. Had Lenin not been at the helm of the party, the Bolsheviks could have lost the opportunity that arose in October.

This importance of leadership was proved in the negative with the defeats of the revolutionary movements in Austria, Hungary, Germany, Italy and elsewhere. Unfortunately, for a variety of different reasons, none of the young Communist Parties that had emerged in this period had leaders of the calibre of Lenin and Trotsky. Hence the urgent task of the Comintern was to help develop such a leadership as the revolutionary process was unfolding, whilst correcting the various mistakes being made.

The defeat of the revolution in Italy and other countries, and especially in Germany, was to have a dramatic impact on Soviet Russia itself, leading to the isolation of the revolution in one country. This was the most important objective factor in the process of the bureaucratic degeneration of the Bolshevik Party, which was also a product of the economic and cultural backwardness of the USSR at the time.

This degeneration found its reflection in the leadership of the Communist International itself. Especially after Lenin’s incapacitation from illness in March 1923, the executive of the Comintern around Zinoviev resorted increasingly to bureaucratic commanding of the leaders of the national sections. Ultimately, by the mid 1930s, the Communist International had been transformed from the vehicle of world revolution, to merely a tool to implement the foreign policy of the Stalinist bureaucracy.

Lessons

The lessons we can draw from the experience of the Communist International in the days of Lenin are twofold. The first is that absolute clarity in theoretical ideas is essential. Make a serious error of analysis, of either an opportunist or a sectarian character, and you can destroy your forces, unless it is corrected. That is why we dedicate so much time and energy to the education of our ranks.

Errors in theory can lead to serious errors in practice. The ultra-leftism of the leaders of the Italian Communist Party in the period 1921-24, for example, played a negative role in isolating the young party from the masses that were still influenced by the reformists of the PSI. In Germany serious errors were committed. Thus a study of that period, together with the classic texts of Lenin is an essential part of the building of our forces today.

The second key lesson is that theoretical rigour and firmness must go hand-in-hand with tactical flexibility. This was an integral part of the Bolshevik Party under Lenin and was encapsulated in the discussions, theses and resolutions adopted by the first four congresses of the Communist International, which Trotsky described as “a school of revolutionary strategy”.

The national sections in the early days of the Communist International were built in different ways, depending on the concrete objective conditions in each country. We must have the same open approach towards the future perspectives today. Not to do so would mean losing opportunities that may present themselves.

As the objective situation changes under the impact of the crisis of capitalism and the tumultuous class struggle that will flow from this, many opportunities will present themselves to significantly increase our forces. But in order to be able to position ourselves correctly will require an educated party, with an understanding of history, with a good grasp of Marxist theory, with the necessary flexibility and the boldness which the situation demands of us.

Our rallying call must be: Back to Lenin! Build Revolutionary Communist Parties now! Forward to the world socialist revolution!