“Without revolutionary theory there can be no revolutionary movement.” (Lenin, What is to be Done?)

A voyage of discovery

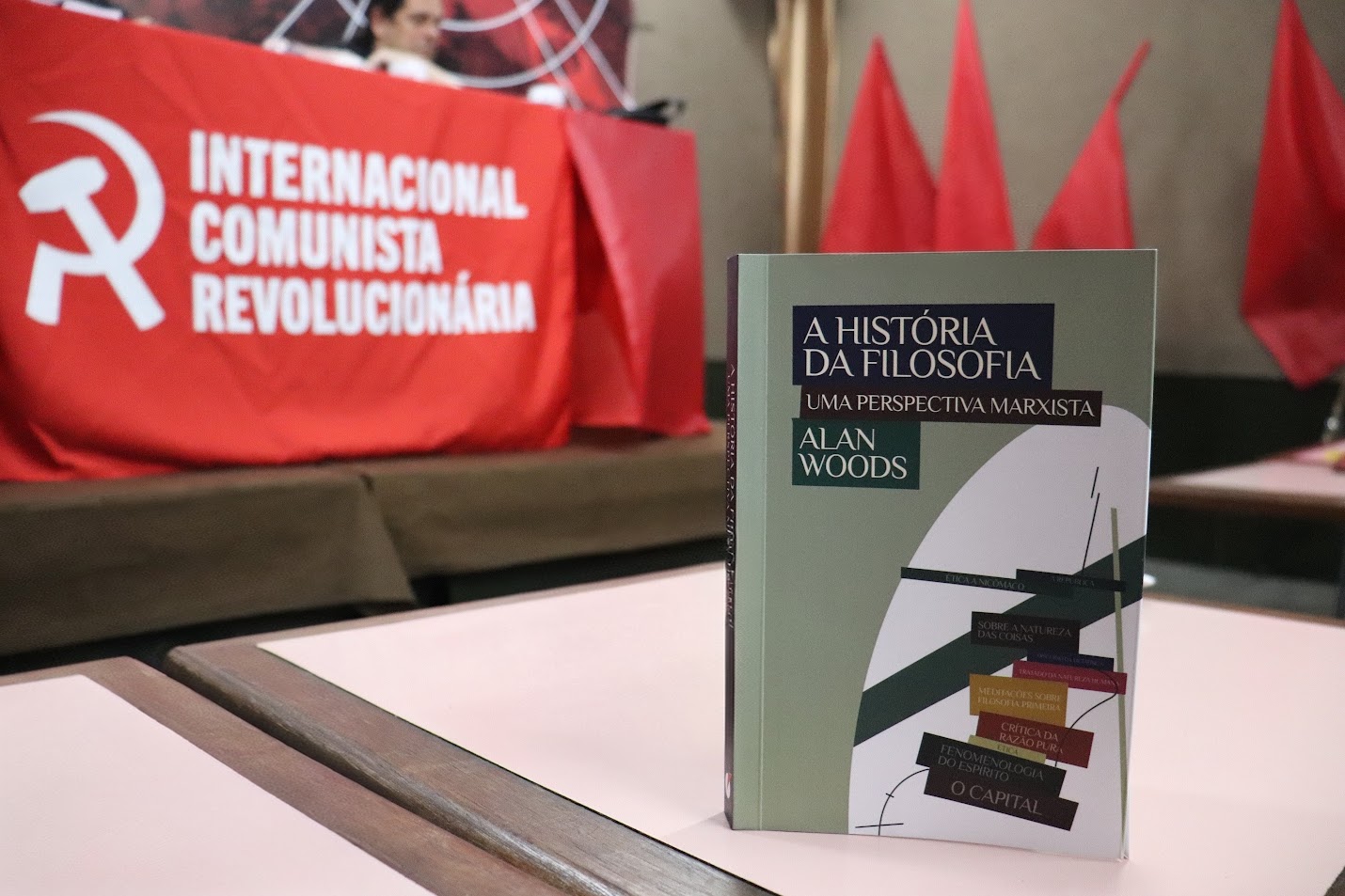

The news of the publication of my book, The History of Philosophy, in Brazil was a moment of great satisfaction for me. It shows that the Brazilian section of the Revolutionary Communist International is being built on sound foundations.

[‘The History of Philosophy’ by Alan Woods can be bought in the original English from Wellred Books here]

It is a clear indication that the Brazilian comrades are eager to study Marxist theory, and in particular philosophy, which is the basis of the method of Marxism – dialectical materialism.

In presenting this book, I invite you to join me on a voyage of discovery. It is a voyage that I began a long time ago and which has not yet come to an end. It is an exciting voyage of ideas that will carry us to many lands and will bring us face to face with many astonishing and original ideas.

We will find ourselves in the presence of some of the most brilliant and original thinkers the world has ever seen. Like any voyage, it will not always be easy.

But I can promise you one thing. If you persist to the end, from that voyage you will emerge enriched. At the end of it, your understanding of the world and society will be far deeper than before.

And you will be far better armed with the ideological weapons that are the indispensable prerequisites for carrying out the revolutionary transformation of society.

That great journey is none other than the history of philosophy.

A scientific world view

Marxism is first of all a scientific world view. It is a powerful weapon that provides us with the necessary tools to analyse and understand the world in which we live. Only if we base ourselves on such an understanding can we change the world. Merely to react to the injustices of capitalism without providing an explanation and analysis of the root causes will lead us nowhere.

The idea that we can get along without some degree of learning is in flat contradiction to everyday experience. In fact, theory is a necessary feature of many aspects of human existence, not just politics.

Every special field of human activity requires a degree of theoretical knowledge. That is true for every conceivable sphere of human existence – from carpentry to brain surgery and rocket science. Why, therefore, should things be any different when it comes to the class struggle?

Do revolutionaries have any right to approach the serious question of revolution with an amateurish approach, which assumes no need for serious study and theoretical preparation?

This is a question which, for any serious person, answers itself.

Despite this, there are some – even some who consider themselves ‘Marxists’ – who consistently deny or downplay the role of theory.

They deny the importance of the ideological struggle, portraying it as the sphere of action of the petty bourgeois intellectuals. Such things, they insist, have nothing to do with the class struggle, with what they call ‘practical politics’, and are therefore of no interest to workers.

A petty bourgeois prejudice

Is it true that workers are not interested in theory, that the sphere of ideas is a monopoly of the petty bourgeois intellectuals?

This idea is not only false. It is a vicious slander against the working class. All my experience has proved beyond doubt that workers have a thirst for theory and ideas.

They are not satisfied with empty agitation. They do not need to be constantly told things that they already know – that they are exploited by the bosses, that they live in bad houses, that society is divided into rich and poor, and so on and so forth.

As somebody from a working-class family in South Wales, I get very angry when I hear that kind of statement. It betrays precisely the mentality of a petty bourgeois snob who has absolutely no knowledge of the workers, how they think and what they aspire to.

Such disgusting snobbishness is entirely alien to communism and has absolutely no place in the ranks of a genuinely proletarian revolutionary organisation.

Serious workers demand an explanation for all these things – and many other things besides. The workers want to know.

And once a worker begins to take a serious interest in Marxist theory, he will become a far more serious theoretician than any middle-class dilettante from the university.

“Ignorance never yet helped anybody”

The argument that workers are not interested in theory is not new. Even before they wrote the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels (who, let us remember, began their revolutionary life as students of Hegelian philosophy) conducted a struggle against those ‘proletarian’ leaders who worshipped backwardness and primitive methods of struggle and stubbornly resisted the introduction of scientific theory into the movement.

The Russian writer, Annenkov, who happened to be in Brussels during the spring of 1846, has left us a very curious report of one meeting at which a furious quarrel occurred between Marx and Weitling, the German utopian communist.

At one point, Weitling, who was a worker, complained that the ‘intellectuals’ (Marx and Engels) wrote about obscure matters of no interest to the workers.

He accused Marx of writing “armchair analysis of doctrines far from the world of the suffering and afflicted people.” At this point, Marx, who was usually very patient, became indignant. Annenkov writes:

“At the last words Marx finally lost control of himself and thumped so hard with his fist on the table that the lamp on it rung and shook. He jumped up saying: ‘Ignorance never yet helped anybody.’” (Pavel Annekov, Reminiscences of Marx and Engels, p.272, my emphasis, AW)

Weitling was opposed to theory and patient propagandistic work. Like Bakunin, he maintained that poor people were always ready to revolt.

This advocate of ‘revolutionary action’ as opposed to theory believed that as long as there were resolute leaders, a revolution could be engineered at any moment. We find echoes of these primitive pre-Marxist ideas even today in the ranks of the Marxists.

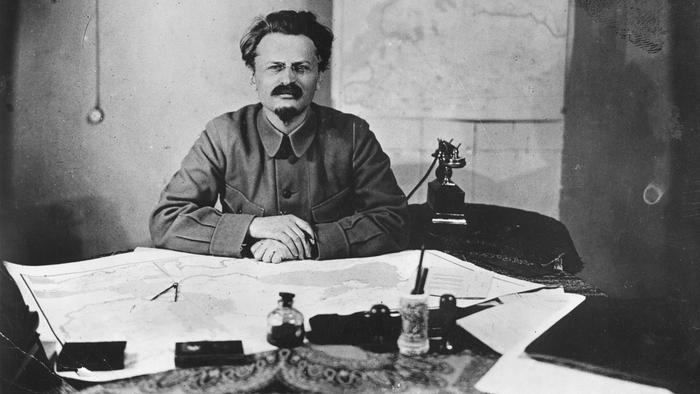

But Marx, Engels, Lenin and Trotsky spent a great deal of time defending and developing Marxist theory, which they correctly understood to be a vital weapon in the revolutionary struggle for socialism.

In defence of Marxism!

Some years ago, the tendency represented by Ted Grant broke from the sectarian group led by Peter Taaffe. Following the split in Britain, we found ourselves in a very difficult situation.

The split coincided with the collapse of Stalinism in the USSR and a ferocious ideological offensive of the bourgeoisie against Marxism and communism. The task ahead of us was extremely challenging.

We had no office, very few funds, and our apparatus consisted of one typewriter. We lacked everything – everything, that is, except for the most important thing of all – correct ideas.

We asked ourselves what our main task was at this time. I discussed this with Ted Grant, and we decided that our main task was to commence a serious ideological struggle in defence of Marxism.

A start was made with the publication of the book Reason in Revolt by Ted Grant and myself.

This book – which has had a very great effect internationally over the years – was, I believe, the first (possibly the only) attempt to provide a theoretical justification of dialectical materialism, and in particular the ideas of Engels’ great philosophical masterpiece, Dialectics of Nature.

Our former comrades in Militant were predictably unimpressed by this. In fact, they found it quite amusing. Why should anyone waste time writing about such matters in this day and age? The leader of that clique of vulgarisers sneered: “Alan and Ted have given up revolutionary politics in order to write about philosophy!”

This little aphorism really tells us everything we need to know about the bankruptcy of those ladies and gentlemen. And in the end, it was the power of ideas that guaranteed our success.

The importance of dialectics

Why did those people consider it unnecessary to write about dialectical materialism? The explanation is not difficult to see.

Such ‘clever’ people pretend to possess a knowledge of dialectics by repeating the word in every other sentence. Oh yes! We all know the basic laws of dialectics! They are so familiar to us, that we can repeat them at a moment’s notice and apply them mechanically to any given situation.

Not long ago I had the misfortune to have to read a very lengthy document that mentions the word dialectics on every page, if not every sentence. Yet there was not a single atom of dialectics in it from the first page to the last. This kind of ‘Marxism’ is really not worth very much.

Far too often, people who consider themselves to be Marxists are satisfied merely to repeat a few elementary propositions, without bothering to study them in all their profundity.

They repeat the word dialectics as a meaningless incantation, much the same way as an aged Catholic priest repeats the Hail Mary, without giving a second thought to the meaning of the words he is mumbling.

They are guilty of a kind of mental laziness, merely skating over the surface, repeating thoughtlessly a few slogans and quotes taken out of context which they have learnt by rote, the genuine content of which remains a closed book for them.

Over time, they have become familiar with some of the basic ideas. But Hegel explained that what is familiar is not understood precisely because it is familiar (“Aber was bekannt ist, ist darum noch nicht erkannt”). Actually, this method is formalism, a very narrow and crude schematism, which has absolutely nothing in common with the scientific method of Marxism.

Lenin’s struggle against the Economist deviation

Lenin’s struggle for theory began at a very early stage of his revolutionary activity, when he sharply criticised the theories of the so-called Economist tendency.

These were people who considered themselves to be ‘practicos’, as opposed to ‘mere theoreticians’. They demanded that the revolutionaries should concentrate exclusively on the practical, day-to-day issues directly affecting workers – principally the economic struggle.

Answering these false ideas, Lenin pointed out that there were three kinds of struggle: economic, political and ideological. All his life he lay heavy stress on the ideological struggle, which began with his struggle against the ‘workerist’ tendency represented by the Russian Economists.

Already in 1902 in What Is To Be Done? Lenin pointed out that:

“Without revolutionary theory there can be no revolutionary movement. This idea cannot be insisted upon too strongly at a time when the fashionable preaching of opportunism goes hand in hand with an infatuation for the narrowest forms of practical activity.” [our emphasis]

He added that “the role of vanguard fighter can be fulfilled only by a party that is guided by the most advanced theory”.

These ideas are just as true today as when they were when Lenin wrote these lines, and just as necessary. Serious workers and youth are seeking the ideas of revolutionary socialism, that is to say, Marxism.

That is why, in addition to the day-to-day struggle for socialism, we pay serious attention to the production of theoretical work. We reject all attempts to ditch Marxist theory, to water down ideas and drag the level of the movement down to the lowest common denominator of mindless ‘activism’.

That represents a fundamental departure from Marxism. The abandonment or neglect of theory, the search for a shortcut to the masses, leads inevitably either to the swamp of opportunism or the dead end of ultra-leftism.

So seriously did Lenin take the ideological struggle that he was prepared to break with the entire leadership of the Bolshevik faction over differences on philosophy.

The split occurred in 1909, when Lenin chose to break with Bogdanov and Lunacharsky rather than make the slightest concession to their revisionism in philosophy and their sectarian formalism and ultra-left politics. This was after almost two years of internal struggle.

However, by the time the split occurred, Lenin had succeeded in winning over the majority of the party to the position of dialectical materialism.

This victory in the ideological plane was precisely the prior condition for the final victory of the Russian proletariat in the October Revolution.

Dogmatic thinking

Marxism is the opposite of dogmatic thinking. The clearest example of that kind of thought is to be found in religion. It is impossible to argue with a committed Christian, who will reply in the words of Tertullian: “Credo quia absurdum est” (I believe because it is absurd).

There is, of course, no answer to this, since it is based on the rejection of rational thought in general. In fact, all religion is based on faith, not logic, and it is impossible to argue against blind faith, precisely because it is blind.

Unfortunately, one sometimes finds a very similar mindset in many sectarian groups who, for some reason, are masquerading under the name of Marxism, and even Trotskyism.

The sectarians, who bear an uncanny similarity to religious fanatics, dig deep into the texts of Marx, Lenin and Trotsky, until, having stumbled across some idea or other that fits in with their preconceived prejudices, they tear it out of its context and present it as an absolute, unchanging and unquestionable truth.

Once it is distorted into a rigid and ossified schema, Marxism is turned into its opposite – from a profound and scientific method into a lifeless dogma that can be mechanically applied to any situation or context that is required.

To cite one example which may be familiar to you: capitalism is unable to develop the productive forces under any circumstances.

Therefore, China cannot have developed the productive forces.

Therefore, China is a backward, undeveloped, dominated semi-colony controlled entirely by the USA.

Therefore, the alleged conflict between China and US imperialism is merely an invention or a figment of the imagination.

The logic of this seems impeccable, and, in fact, it faithfully follows the rules of formal logic. Once one accepts the initial proposition, the rest follows, as night follows day. For example:

All scientists have two heads.

Einstein was a scientist.

Therefore, Einstein had two heads.

Is that ridiculous? Obviously, it is, because it does not correspond to the known facts. But as an example of formal logic, it is a perfectly reasonable example of Aristotelian syllogism, and, as such, must be accepted as correct.

The problem is, of course, that the initial proposition is false, and therefore, the whole thing falls to the ground.

This is also true of the proposition that capitalism is not capable under any circumstances of developing the productive forces, since it has done so on many occasions, notably, in the period following the Second World War.

The theory that, in the age of imperialism, no development of the productive forces is possible, is regarded as an absolute proposition valid for all time – a magical key that opens all doors.

It is based on a misinterpretation of what Trotsky wrote in 1938 in The Transitional Programme, where he pointed out that the productive forces had ceased to grow.

That was correct at that time. But Trotsky never claimed that this was a proposition that had a universal application, independent of time and space.

In fact, he warned against this in advance:

“But a prediction in politics does not have the character of a perfect blueprint; it is a working hypothesis… One must not, however, get intoxicated with finished schemata, but continually refer to the course of the historic process and adjust to its indications.” (Trotsky, Writings, 1930, p.50)

By turning what was a conditional prognosis into an absolute assertion, valid for all time and applicable in all circumstances, the sectarians have turned Trotsky’s scientific analysis into complete nonsense.

Capitalism is not eternal or fixed. In fact, it is less fixed than any other socio-economic system in history. Like any other living organism it changes, evolves and therefore passes through a number of more or less clearly discernible stages.

In the debates at the Third Congress of the Communist International in 1921, Trotsky intervened against the ultra-lefts who rejected the idea that capitalism would never experience an economic recovery.

And Lenin insisted that there was no such thing as a final crisis of capitalism. Unless it is overthrown by the proletariat, capitalism will always find its way out of even the deepest economic crisis.

And this was clearly demonstrated by the revival of the system following the end of the Second World War, when the productive forces experienced an upswing that surpassed even that of the Industrial Revolution.

This is not the place to develop an argument which we have already done comprehensively elsewhere. Suffice it to say that the entire method used to ‘prove’ that China has not developed the productive forces is false from start to finish.

But to argue with such people is quite useless, since no matter how many facts you can produce to prove that they are wrong, they will always invariably assert that 2+2 = 5, and not four.

And since their dogma is right, if it is contradicted by reality, then reality, by definition, must be wrong.

It goes without saying that any similarity between this method and the dialectical method of Marxist dialectical materialism is purely accidental.

Building on sand

To those who imagine that they can build a serious revolutionary movement without theory, we can only answer with a resigned shrug of the shoulders. We might as well remind them of the words of the Bible:

“…like unto a foolish man, which built his house upon the sand: And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell: and great was the fall of it.”

Real communists must build a house on solid foundations:

“And the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house; and it fell not: for it was founded upon a rock.”

The rock of which the Bible speaks is the rock of religious faith. Naturally, we have no need whatsoever for that. The rock on which we build our organisation is the granite rock of Marxist theory.

Today we are proud to say that the Revolutionary Communist International is the only tendency in the world that has consistently defended Marxist theory.

Without theory, we would have no reason to exist as a separate political tendency. It is what distinguishes us, on the one hand, from the reformists of both the left and right variety, and on the other hand from the sectarian muddleheads.

Books like Reason in Revolt have become a cornerstone for the defence of dialectical materialism, specifically in the field of modern science, where it follows closely in the footsteps of Engels’ great theoretical works: Anti-Dühring and the Dialectics of Nature.

And The History of Philosophy represents a similar advance in the defence of Marxist theory.

Why study the history of philosophy?

In order to arrive at a full understanding of dialectical materialism, a great deal of careful study will be necessary.

But there is a difficulty involved in the study of philosophy in general, and Marxist philosophy in particular – and one that lies at the heart of the book I am presenting to you today.

When Marx and Engels wrote about dialectical materialism, they could presuppose a basic knowledge of the history of philosophy on the part of at least the educated reading public of the day.

Nowadays, unfortunately, it is impossible to make such an assumption. I feel very sorry for the students of philosophy today.

The bright-eyed young students who enter the philosophy department with high hopes of enlightenment are either swiftly disenchanted or else they are dragged into the poisonous cesspool of postmodern gibberish from whence no escape is possible. In either case, they will emerge without ever learning anything of value from the great thinkers of the past.

Not content with filling the minds of young people with postmodernist rubbish, they have the audacity to introduce the same garbage into the study of the history of philosophy.

These postmodern pygmies have the audacity to treat the great thinkers of the past with contempt because they do not fit into their nonsense.

This is no accident.

The senile decay of modern bourgeois philosophy

Evidently, the High Priests of postmodernism do not like to be reminded of the fact that there was once a time when philosophers actually had something profound and important to say about the real world.

There were many such examples. In the past philosophers were rebels and heroes.

Socrates was forced to drink a cup of poisonous hemlock because he defied the existing ideas of society.

Giordano Bruno was sentenced to be burned to death by the Roman Inquisition for his heretical ideas, which he refused to recant.

The materialist philosophers of the Enlightenment prepared the way for the French Revolution. But nowadays the situation is quite different.

The attitude of most people to philosophy is one of contempt, or rather of complete indifference. This is well deserved. Modern bourgeois philosophy presents a truly lamentable spectacle, to quote Shakespeare:

“Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion;

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.”

Here we have a suitable epitaph to place on the grave of modern bourgeois philosophy.

The significance of the history of philosophy

Yet it is unfortunate indeed that in turning aside from the present-day philosophical desert, people neglect the great thinkers of the past who, in contrast to the modern dilettantes, were giants of human thought.

In the history of philosophy, there have been many schools of thought, not a few of them brilliantly original, which serve to illuminate this or that aspect of the truth. But not one of these philosophical systems, taken in isolation, was capable of revealing the whole truth.

The brilliance of Hegel was to conceive of the entire history of philosophy as a single process of thought, of what he calls Self-consciousness.

Hegel treated the history of philosophy, not as a senseless sequence of disconnected ideas by individual thinkers, but as an organic whole, in which each stage negates the previous stage, but at the same time preserves all that is necessary and valid in its real content, raising it to a higher level.

This was finally achieved by Marx and Engels who, setting out from the materialist analysis of Hegel’s dialectic, accomplished a great revolution, which marked the emergence of philosophy out of the dark, stale atmosphere of the study, into the brilliant sunshine, air and light of the day.

It was this great philosophical revolution that provided the real basis for the future victory of the proletarian revolution. And it did not drop from the sky, but was the final product of many generations of the most advanced and brilliant thinkers in the history of the world.

Marxism has a duty to provide a comprehensive alternative to the old and discredited ideas. But we have no right to turn our backs on the great thinkers of the past, those heroes who paved the way for all the great advances of modern science.

We have a duty to rescue all that was valuable in the history of philosophy, while discarding all that was false, outmoded and useless.

One can learn a great deal from the Greeks, Spinoza, the French materialists of the Enlightenment and above all Hegel.

These were heroic pioneers, who prepared the way for the brilliant achievements of Marxist philosophy and can rightly be considered as an important part of our revolutionary heritage.

The algebra of revolution

The Russian revolutionary Alexander Herzen once described Hegel’s dialectic as the algebra of revolution. That was well said.

In order to solve the most urgent problems of society, the entire edifice of capitalism must be overthrown.

But in order to speed up the demolition of this rotten system, it is necessary to clear the ground by demolishing the rotten ideology that is propping it up.

This shows the vital importance of understanding the ideas that have been shaped over a lengthy period of history.

To this day, philosophy remains a battlefield over which the two antagonistic and mutually incompatible schools of materialism and idealism continue to fight it out.

Just as we pay careful attention to the lessons afforded by the great class struggles of the past, so we have a duty to study the great battle of ideas that constitutes the essential meaning of the history of philosophy.

Just as the October Revolution, the Paris Commune and the storming of the Bastille pointed the way to the future socialist revolution that will transform the entire world, so the great philosophical battles of the past laid the basis for dialectical materialism – the philosophy of the future.

It is for that reason that I wrote the present work. It is dedicated to the new generation of young revolutionaries who are eager to study and learn the ideas of genuine communism.

An important part of the education of our young cadres is a careful study of the history of philosophy. If my book can serve to stimulate and encourage you to do so, it will have achieved its purpose.

I wish you a fruitful and enjoyable journey.

Bon voyage!

London, 15 October 2025