One-hundred-and-seven years ago, on 7 November 1917, the Russian working class conquered power.

This was the greatest event in human history. For the first time ever, workers and peasants overthrew the dictatorship of the rich, took control of society themselves, through their ‘soviets’, i.e. workers’ councils – and held it. They could not have done so, however, without the leadership of the Bolshevik Party; the party of Lenin and Trotsky.

To commemorate the anniversary of this momentous, world-historic event, and to arm communists today with the ideas that enabled the conquest of power, we are republishing an extract from Alan Woods and Rob Sewell’s biography of the great revolutionary, In Defence of Lenin.

This extract, taken from the second volume of the book, covers Lenin’s struggle within the party to prepare it for the insurrection, and the revolutionary overturn itself.

The November insurrection, however, was only the climax of Lenin and the Russian communists’ long struggle to build a revolutionary, working-class party, and to win the leadership of the revolutionary movement.

To read about this struggle, and to learn how the Bolsheviks acted in power, at the head of the world’s first workers’ state, get your copy of In Defence of Lenin from Wellred Books, the publishing house of the Revolutionary Communist International.

By the end of September, the situation had undergone a complete transformation as the pendulum swung sharply to the left. The reformist leaders of the Mensheviks and SRs had – unsurprisingly – dismissed as ‘fanciful’ the Bolsheviks’ offer of a peaceful transfer of power within the Soviets. There was no longer going to be any progress on that front. In the meantime, Kerensky and his ‘socialist’ government were becoming more unpopular by the day. The initiative was now firmly in the hands of the Bolshevik leadership. The fate of the insurrection hung in the balance.Lenin made his way to Petrograd on 22 October. This was to be only a little over two weeks before the Bolshevik insurrection would take place, but few, apart from Lenin, realised the urgency of the situation.

The objective conditions had fully developed for a decisive showdown. Lenin now had to convince the Bolshevik leadership to draw the necessary conclusions and act accordingly. But even at this late stage, this proved to be no easy task.

On 23 October, Lenin was to attend the crucial meeting of the Central Committee where the insurrection was on the agenda. Ironically, the venue of this historic meeting was in the house of Sukhanov, the Left Menshevik, which had been made available by his wife, a Bolshevik sympathiser.

Lenin had not attended a single Central Committee meeting since first going into hiding in early July. That now seemed an eternity away. He had moved from Finland to live secretly in a suburb of Petrograd, in order to be closer to the centre of operations. He clearly saw that time was pressing and the insurrection could not be delayed any longer. Lenin’s campaign of relentless pressure found its expression in a stream of letters to the leadership demanding an insurrection.

There are moments in which a few days, or even hours, can mean the difference between victory and defeat. This is just as true in a revolution as in normal warfare. The masses could not be kept permanently in a state of expectation. Further prevarication could lead to a fatal loss of impetus. The precise calculation of the right moment to launch a decisive offensive is the essence of what Trotsky called the art of insurrection. And Lenin, like Trotsky, was a master of that art.

Following a tense discussion, the Central Committee meeting adopted Lenin’s proposal to prepare for an immediate armed insurrection by a majority of ten votes – Lenin, Trotsky, Sverdlov, Stalin, Uritsky, Felix Dzerzhinsky, Kollontai, Grigory Sokolnikov, Andrei Bubnov and Lomov (Georgy Oppokov). But two prominent members of the Central Committee voted against – Kamenev and Zinoviev. And quite a few others, though they voted for the resolution, did so with reservations.

“We are practically approaching the armed insurrection. But when will it be possible? Perhaps a year from now – one can’t really tell”, pondered Mikhail Kalinin. Vladimir Milyutin, a member of the Central Committee, also added his voice to the doubters: “We are not ready to strike the first blow. We are in no position to overthrow the government or stop its supporters in the days to come.”[1]

Sukhanov was later briefed about the meeting. Referring to Lenin as the ‘Thunderer’, he commented about what had happened in the following terms:

“In the Central Committee of the Party this decision was accepted by all but two votes. The dissenters were the same as in June – Kamenev and Zinoviev… This of course could not confound the Thunderer. He had never been confounded even when he remained practically alone in his own party; now he had the majority with him. And, besides the majority, Trotsky was with Lenin. I don’t know to what degree Lenin himself valued this fact, but for the course of events it had incalculable significance. I have no doubt of that…” [2]

There were, nevertheless, still some loose ends and the exact date of the seizure of power was still left hanging in the air. The Second National Congress of Soviets was scheduled for 2 November (20 October, Old Style), where the Bolsheviks were guaranteed a majority. It was therefore assumed that an insurrection should begin sooner, certainly not later than around 28 October. But that schedule only gave them five days to finalise everything, which was deemed insufficient. It was therefore agreed that another Central Committee meeting would take place on 29 October to finalise matters.

Opposition of Kamenev and Zinoviev

Following the Central Committee of 23 October, Zinoviev and Kamenev sent a personal statement of their opposition to an insurrection to Central Committee members, while sending a circular, entitled ‘On the Current Situation’, to a number of Bolshevik organisations. This read:

“We are deeply convinced that to proclaim an armed insurrection now is to put at stake not only the fate of our Party but also the fate of the Russian and the international revolution.

“There is no doubt that historical circumstances do exist when an oppressed class has to recognise that it is better to go on to defeat than surrender without a fight. Is the Russian working class in just such a position today? No, a thousand times no!! […]

“The influence of Bolshevism is growing. Whole sections of the working population are still only beginning to be swept up in it. With the right tactics, we can get a third of the seats in the Constituent Assembly, or even more.” [3]

It was abundantly clear that Zinoviev and Kamenev simply envisaged the role of the Bolshevik Party as an opposition group in the Constituent Assembly / Image: public domain

It was abundantly clear that Zinoviev and Kamenev simply envisaged the role of the Bolshevik Party as an opposition group in the Constituent Assembly. This statement, coming from leading members, led to some confusion within the ranks of the Party. To counter this, Lenin immediately wrote two letters directly to the membership over the following few days. In them, he attacked Zinoviev and Kamenev, but without naming them:

“Only a most insignificant minority of the gathering, namely, all in all two comrades, took a negative stand. The arguments which those comrades advanced are so weak, they are a manifestation of such an astounding confusion, timidity, and collapse of all the fundamental ideas of Bolshevism and proletarian revolutionary internationalism that it is not easy to discover an explanation for such shameful vacillations. The fact, however, remains, and since the revolutionary party has no right to tolerate vacillations on such a serious question, and since this pair of comrades, who have scattered their principles to the winds, might cause some confusion, it is necessary to analyse their arguments, to expose their vacillations, and to show how shameful they are.”[4]

Lenin then answered the objections that somehow the uprising was hopeless, and that the Bolsheviks should therefore wait for the summoning of the Constituent Assembly, so as to form a strong opposition, and so on. This ‘peaceful’ parliamentary perspective was wholly at odds with Lenin’s perspective of taking power and therefore he felt the need to pose things very sharply: either they – the Bolsheviks – would immediately seize power or a military dictatorship, not a Constituent Assembly, would be established:

“Let us forget all that was being and has been demonstrated by the Bolsheviks a hundred times, all that the six months’ history of our revolution has proved, namely, that there is no way out, that there is no objective way out and can be none except a dictatorship of the Kornilovites or a dictatorship of the proletariat.” [5]

He then continued to ridicule the route of the Constituent Assembly:

“Let us forget this, let us renounce all this and wait! Wait for what? Wait for a miracle, for the tempestuous and catastrophic course of events from 20 April to 29 August to be succeeded (due to the prolongation of the war and the spread of famine) by a peaceful, quiet, smooth, legal convocation of the Constituent Assembly and by a fulfilment of its most lawful decisions. Here you have the ‘Marxist’ tactics! Wait, ye hungry! Kerensky has promised to convene the Constituent Assembly.”[6]

In regard to the accusation of Blanquism made against the proposed insurrection, Lenin replied:

“Marxism is an extremely profound and many-sided doctrine. It is, therefore, no wonder that scraps of quotations from Marx – especially when the quotations are made inappropriately – can always be found among the ‘arguments’ of those who break with Marxism. Military conspiracy is Blanquism, if it is organised not by a party of a definite class, if its organisers have not analysed the political moment in general and the international situation in particular, if the party has not on its side the sympathy of the majority of the people, as proved by objective facts, if the development of revolutionary events has not brought about a practical refutation of the conciliatory illusions of the petty bourgeoisie, if the majority of the Soviet- type organs of revolutionary struggle that have been recognised as authoritative or have shown themselves to be such in practice have not been won over, if there has not matured a sentiment in the army (if in war-time) against the government that protracts the unjust war against the will of the whole people, if the slogans of the uprising (like ‘All power to the Soviets’, ‘Land to the peasants’, or ‘Immediate offer of a democratic peace to all the belligerent nations, with an immediate abrogation of all secret treaties and secret diplomacy’, etc.) have not become widely known and popular, if the advanced workers are not sure of the desperate situation of the masses and of the support of the countryside, a support proved by a serious peasant movement or by an uprising against the owners and the government that defends the owners, if the country’s economic situation inspires earnest hopes for a favourable solution of the crisis by peaceable and parliamentary means.” [7]

Lenin ends his letter: “This is probably enough.”[8] He had made everything clear.

With the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee under the control of the Bolsheviks, and Trotsky at its head, the pieces were being put into place for a successful insurrection. This was the situation facing the extended Central Committee meeting, held on 29 October, and attended by representatives from the Petrograd committee, the military organisation, and the factory committees.

At this meeting, Lenin once again forcefully argued for an insurrection without any delay. “The masses had put their trust in the Bolsheviks and demanded deeds from them, not words”, he argued. [9] If we take power now, he said, “the Bolsheviks would have all proletarian Europe on their side”, once again linking the Russian revolution to the European revolution.[10]

But Zinoviev and Kamenev pressed their opposition, demanding that the decision be postponed until after the Soviet Congress so as to ‘confer’ with delegates from the provinces. In any case, they believed the plans for the insurrection were not sufficiently serious, as little had been prepared. Kamenev stated:

“A week has passed since the resolution was adopted and this is also the reason this resolution shows how not to organise an insurrection: during that week, nothing was done; it only spoiled what should have been done. The week’s results demonstrate that there are no factors to favour a rising now.”[11]

Tempers became quite heated within the meeting. However, in the end, it was agreed by twenty-two votes in favour and two against – again the votes of Zinoviev and Kamenev – to endorse the resolution of the 23 October and proceed with the planned insurrection. But time was clearly running out.

Fortunately, unbeknown to them, the Mensheviks and SRs came to the rescue. For their own reasons, they decided to postpone the Soviet Congress until 7 November (25 October, Old Style). This extra week proved indispensable.

In the biography of Stalin prepared by the Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute in Moscow in 1940, a spurious claim is made: “On 16 (29) October, the Central Committee elected a Party Centre, headed by Comrade Stalin, to direct the uprising.”[12] While it is true that the Central Committee did elect a ‘Centre’ to assist the insurrection, this body never actually met! It was simply overtaken by events and relegated to the waste paper basket.

Control of the October insurrection was in the hands of the Military Revolutionary Committee, under Trotsky’s direction.

‘Strike-breaking’

At the end of the Central Committee of October 29, Kamenev, having opposed the insurrection, announced his resignation from the Central Committee. Two days later, on 31 October, Kamenev and Zinoviev attacked the whole idea of an insurrection publicly in an article in Maxim Gorky’s paper, Novaya Zhizn.

When their fellow comrades heard this news, they were stunned. Not only was this a complete breach of discipline and trust, but it was a clear warning to the enemies of the Party of their plans for an insurrection. This was the worst kind of betrayal – a stab in the back on the eve of battle.

Once Lenin heard the news, he was beside himself with rage at this outrageous behaviour. He immediately wrote a letter to the membership denouncing it:

“This is a thousand times more despicable and a million times more harmful than all the statements Plekhanov, for example, made in the non-Party press in 1906-07, and which the Party so sharply condemned! At that time it was only a question of elections, whereas now it is a question of an insurrection for the conquest of power!”[13]

He then wrote in another letter to the Central Committee: “No self-respecting party can tolerate strike-breaking and blacklegs in its midst.”[14] He then called for the expulsion of Zinoviev and Kamenev from the Party. The next day he wrote a further letter, elaborating on the first.

Up until this point, Kamenev and Zinoviev were the ‘old Bolsheviks’, Lenin’s closest Party comrades, who had been with him for many years. Zinoviev was personally with Lenin throughout the war years. And yet, when faced with the decisive question of power, they politically collapsed.

Up until this point, Kamenev and Zinoviev were the ‘old Bolsheviks’, Lenin’s closest Party comrades, who had been with him for many years / Image: public domain

In an attempt to limit the public damage, Trotsky tried to disguise the insurrection by refuting the allegations. However, in doing so, he also added that any attempt by the counter-revolution to disrupt the Soviet Congress would be met with the severest measures. In the end, Kamenev had no alternative but to go along with Trotsky’s public explanation.

However, to add to the confusion, the Pravda editors, after publishing a brief statement by Zinoviev, added an extraordinary statement from themselves, downplaying the betrayal. It even criticised Lenin for his tone! “The matter may be considered closed. The sharp tone of comrade Lenin’s article does not change the fact, fundamentally, we remain of one mind.” [15] It turned out that it was Stalin, as one of the editors, who was responsible for this statement.

At the Central Committee meeting of 3 November, Lenin was not present. His letter, however, condemning Zinoviev and Kamenev, was read out. But those present took a very lenient view. Stalin immediately declared that as far as Lenin’s proposal was concerned, “expulsion from the Party was no remedy, what is needed is to preserve Party unity…” Therefore, Kamenev and Zinoviev should not be expelled, but should remain as members of the Central Committee.[16]

After some discussion, Kamenev’s resignation from the Central Committee was accepted and Zinoviev and Kamenev were simply instructed to make no further announcements. Following the objections from Stalin, Miliutin, Uritsky and Sverdlov, Lenin’s proposal to expel Zinoviev and Kamenev was also turned down. This was an exceptionally mild rebuke under the circumstances!

Trotsky, however, not only denounced their strike-breaking behaviour in the meeting, but he also attacked Stalin’s mealy-mouthed statement in Pravda. In response, Stalin offered his resignation, but this was brushed aside as the Pravda statement was deemed not to be from him personally, but from the whole editorial board and the meeting merely passed on to the next business.

When he heard all of this, Lenin, it should be noted, did not agree with these decisions, but accepted them so as to concentrate everything on the success of the impending insurrection.

The October insurrection

Despite the damage, it was agreed that the insurrection would still take place before the opening of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets. Nevertheless, Lenin was still opposed to linking the date of the insurrection to the Soviet Congress, fearing it would be postponed and the opportunity missed. Lenin’s fears were not without foundation as the Menshevik leaders, who controlled the Soviet Executive Committee, were definitely seeking to delay matters. Morgan Price writes:

“I found members of the Executive very depressed. Reports from the provinces showed that the Bolshevik agitation for an immediate summoning of a Second Congress had met with great response… They had done, said the Menshevik Central Executive, everything to prevent the summoning of this Second Soviet Congress because they considered it useless.”[17]

In reality, they knew they were in a minority and were destined to lose their positions once the Congress took place.

Trotsky, however, was in favour of this date. Due to his pivotal position, he was more in tune with the situation than most. Given the pressure from below, he firmly believed the Congress would proceed as planned on 7 November, which would give the insurrection greater legitimacy in the eyes of the masses, a ‘legality’, than if the Party carried it out alone. In the end, Trotsky was proved to be correct as he energetically directed the military operations of the insurrection.

Up to the very last minute, Lenin was understandably on tenterhooks. He, more than anyone else, realised the importance of the moment. His whole life’s work was concentrated in these days and hours. He understood that any delay by the Party could end in ruin and that everything was now in the balance. “Now or never!” he repeated.

Even the day before the insurrection, Lenin was still pleading for the Central Committee to act! “The government is tottering”, he wrote. “It must be given the death-blow at all costs. To delay action is fatal.”[18] In fact, it was the Provisional Government that moved first by ordering two Bolshevik offices to be closed down. This played into the hands of the insurrectionists, who used this to go onto the offensive.

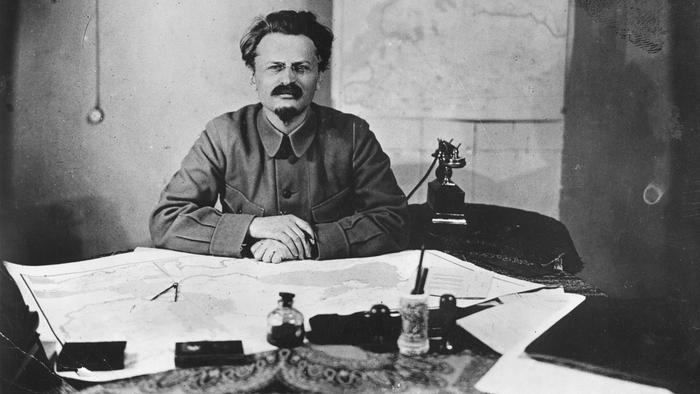

Due to his pivotal position, Trotsky was more in tune with the situation than most / Image: public domain

Lenin, feeling increasingly anxious, defied the orders of the Central Committee and made his way over to Smolny, the headquarters of the Soviet. However, by this time, Trotsky had things firmly in hand and the insurrection was well under way.

During the night of 6-7 November (24-25 October, Old Style), the Military Revolutionary Committee deposed the Kerensky Government and carried through a smooth and peaceful transition of power – just in time for the opening of the Soviet Congress. All the key points of Petrograd were occupied and members of the Provisional Government had been arrested or had fled the scene. “The city was absolutely calm”, writes Sukhanov. “Both the centre and the suburbs were sunk in a deep sleep, not suspecting what was going on in the quiet of the cold autumn night.”[19]

Once the Winter Palace had fallen, the old regime was finally at an end. “The operations, gradually developing, went so smoothly that no great forces were required”, explains Sukhanov.[20] The insurrection was so peaceful, even compared to the February Revolution, that there were only five casualties, all from the ranks of the revolutionaries. This was the most bloodless revolution in history.

“The Provisional Government is deposed”, read the statement issued by the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies at ten o’clock in the morning of 7 November:

“The State Power has passed into the hands of the organ of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, the Military Revolutionary Committee, which stands at the head of the Petrograd proletariat and garrison. […]

“Long live the revolution of the workers, soldiers, and peasants!”[21]

According to one witness:

“All practical work in connection with the organisation of the uprising was done under the immediate direction of Comrade Trotsky, the President of the Petrograd Soviet. It can be stated with certainty that the Party is indebted primarily and principally to Comrade Trotsky for the rapid going over of the garrison to the side of the Soviet and the efficient manner in which the work of the Military Revolutionary Committee was organised. The principal assistants of Comrade Trotsky were Comrades Antonov and Podvoisky.”[22]

The writer was none other than Joseph Stalin. However, in a speech delivered to the Plenum of the Communist Fraction of the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions six years later, Stalin paints a totally different picture:

“Comrade Trotsky, who was a relative newcomer in our Party in the period of October, did not, and could not have played any special role either in the Party or in the October uprising.”[23]

Stalin’s depiction of events had changed by 1924, as this was the year that an all-out struggle took place against Trotsky, to denigrate his achievements and prevent him from assuming the leadership after Lenin’s death.

The Congress opens

From the early morning of 7 November, the Smolny Institute began to fill with delegates. As the opening of the Congress was continually delayed, caucus and faction meetings repeatedly took place throughout the day. By three o’clock in the afternoon, the Great Hall was full of representatives from all parts of the country waiting in anticipation for the grand opening. But there was a further delay, as the Winter Palace had not yet been taken. Then, at twenty to eleven at night, as the Red Guards stormed the Winter Palace, the Congress finally opened.

From the very outset, a packed Smolny resounded with rallying speeches and enthusiastic appeals. It became clear that the Bolsheviks and their allies were in a large majority. According to estimates, the Bolsheviks held 390 seats out of a total of 650. The SRs held between 160 to 190 seats, but they had already split into left and right factions. The Mensheviks, which in June had 200 delegates, were now reduced to less than half, with only sixty to seventy. It was certain that an overwhelming majority of delegates favoured the insurrection and the seizure of power by the Soviets.

From the very outset, a packed Smolny resounded with rallying speeches and enthusiastic appeals / Image: public domain

But the old members of the Congress Executive Committee still reflected the previous balance of forces. This meant that the first part of the proceedings was presided over by the outgoing Committee, dominated by the Mensheviks and SRs, with Fyodor Dan in the chair. “We have met under the most peculiar circumstances”, he said in his opening remarks. “On the eve of the elections for the National Assembly the Government has been arrested by one of the parties in this Congress. As a spokesman of the old Executive I declare this action to be unwarranted.”[24] But his opinions fell on deaf ears.

The delegates moved to elect a new chairman, with the Bolshevik, Sverdlov, taking charge of proceedings. Suddenly, an SR member jumped up to protest that three comrades of his party were at that very instant under siege in the Winter Palace. “We demand their immediate release!” he proclaimed.

This was answered by Trotsky, who immediately went to the rostrum. He replied that the outburst was completely hypocritical, as it was the SRs who shared responsibility for the arrest of a number of Bolsheviks, as well as permitting the spying activities on the Bolshevik Party by the old secret police! With Trotsky’s reply, the whole hall erupted in general tumult.

The Mensheviks and right-wing SRs were feeling the ground shifting under their feet. They therefore moved that negotiations be immediately opened by the Soviet with the Provisional Government to establish a new Coalition government. But they also made it clear that the Bolsheviks, who they accused of being responsible for the ‘adventure’, would never be allowed to share power.

As expected, this proposal fell flat, since the Mensheviks and SRs were in a small minority at the Congress. Despite appeals from Martov, the Mensheviks and the Bund delegates, realising their impotence, walked out, taking around 20 per cent of the hall with them. As they left, they were met with cat-calls and jeers from all sides. Everyone felt that with this action, the Rubicon had been crossed.

At that moment, the platform read out that the Provisional Government had been arrested, which provoked stormy jubilation. Then, with a sea of hands, the delegates ratified the transfer of state power to the Soviet, followed by ecstatic cheers of celebration. Amid the noise and commotion, Martov tried to speak as if nothing had happened. His proposal for a coalition of all socialist parties, including those opposed to the seizure of power, was again met with derision. Then Trotsky once again took the floor.

“The masses of the people have followed our banner, and our insurrection was victorious. And now we are told: Renounce your victory, make concessions, compromise. With whom? I ask with whom ought we to compromise? With those wretched groups who have left us…? But we have seen through them completely. No one in Russia is with them any longer. Should those millions of workers and peasants represented in this Congress make a compromise, as between equals, with the men who are ready, not for the first time, to leave us at the mercy of the bourgeoisie? No, here no compromise is possible. To those who have left, and to those who suggest it to us, we must say: You are miserable bankrupts, your role is over; go where you ought to be – into the dustbin of history.”[25]

Martov, angered by this intervention, shouted from the platform: “Then, we’ll leave as well.”[26] And so his supporters walked out.

“Lenin was not present at it”, explained Trotsky, relating to the first session of the Congress.

“He remained in his room at Smolny, which, according to my recollection, had no, or almost no furniture. Later someone spread rugs on the floor and laid two cushions on them. Vladimir Ilyich and I lay down to rest. But in a few minutes I was called: “Dan is speaking; you must answer.” When I came back after my reply I again lay down near Vladimir Ilyich, who naturally could not sleep. It would not have been possible. Every five or ten minutes someone came running in from the session hall to inform us what was going on there…

“It must have been the next morning, for a sleepless night separated it from the preceding day. Vladimir Ilyich looked tired. He smiled and said, “The transition from the state of illegality, being driven in every direction, to power – is too rough.” “It makes one dizzy”, he at once added in German, and made the sign of the Cross before his face. After this one more or less personal remark that I heard him make about the acquisition of power he went about the tasks of the day.”[27]

Lenin speaks

John Reed, the American journalist and Communist, was present at the Congress. He recalled the events in his celebrated classic, Ten Days That Shook the World, to which Lenin wrote a preface “recommending it to the workers of the world…” Reed described the scene at the second session of the Congress where Lenin was about to speak:

“It was 8.40 when a thunderous wave of cheers announced the entrance of the praesidium, with Lenin – great Lenin – among them. A short, stocky figure, with a big head set down on his shoulders, bald and bulging. Little eyes, a snubbish nose, wide generous mouth, and heavy chin; clean-shaven now but already beginning to bristle with the well-known beard of his past and future. Dressed in shabby clothes, his trousers much too long for him. Unimpressed, to be the idol of a mob, loved and revered as perhaps few leaders in history have been. A strange popular leader – a leader purely by virtue of intellect; colourless, humourless, uncompromising and detached, without picturesque idiosyncrasies – but with the power of explaining profound ideas in simple terms, of analysing a concrete situation. And combined with shrewdness, the greatest intellectual audacity.”

After some interventions, Lenin rose to speak. John Reed continues:

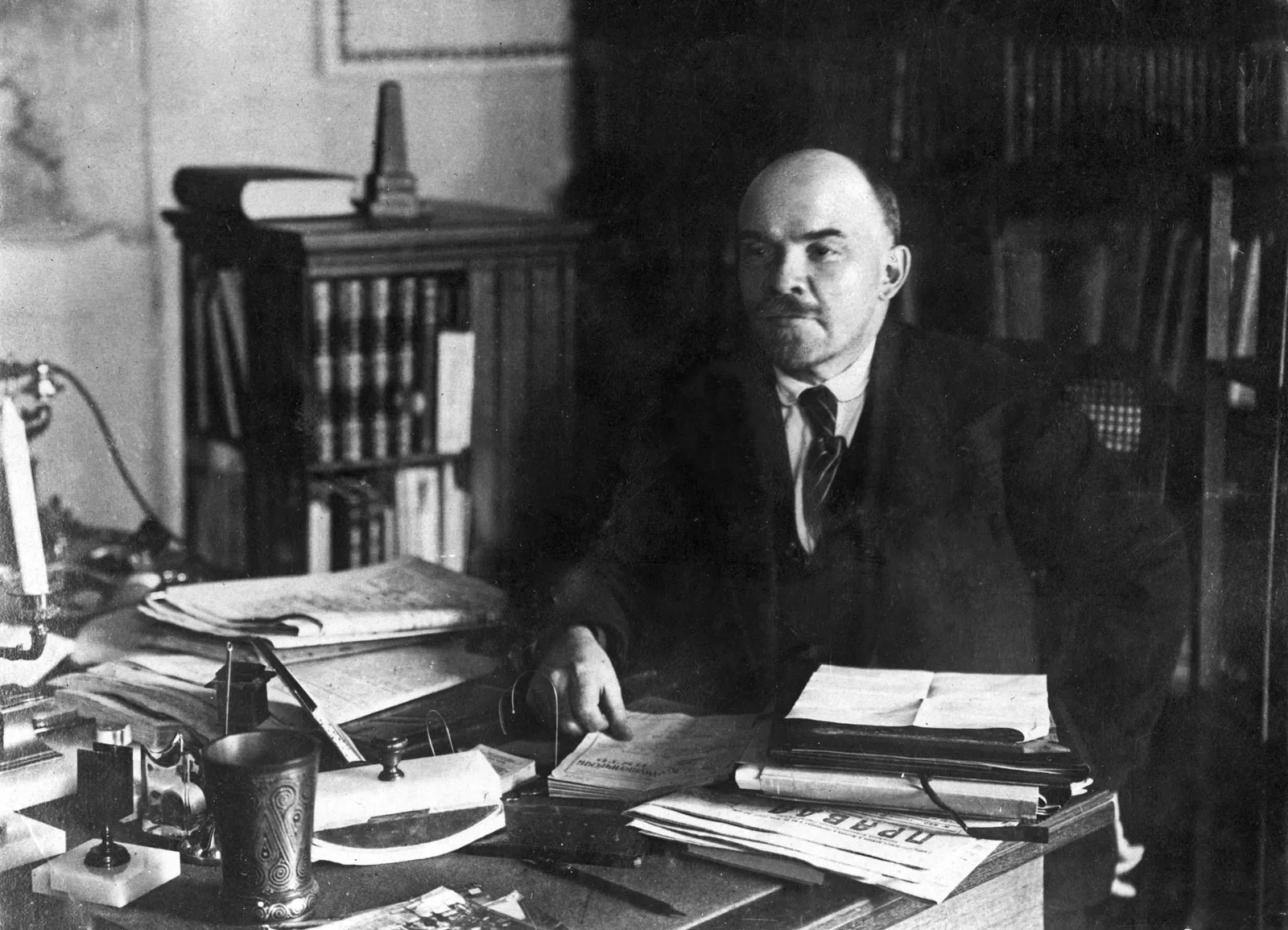

The following day it was announced, amid loud and prolonged cheers, that Lenin was chosen, without portfolio, as Chairman of the new government / Image: public domain

“Now Lenin, gripping the edge of the reading stand, letting his little winking eyes travel over the crowd as he stood there waiting, apparently oblivious to the long- rolling ovation, which lasted several minutes. When it finished, he said simply, ‘We shall now proceed to construct the Socialist order!’ Again that overwhelming human roar.

“‘The first thing is the adoption of practical measures to realise peace… We shall offer peace to the peoples of all belligerent countries upon the basis of Soviet terms – no annexations, no indemnities, and the right of self-determination of peoples. At the same time, according to our promise, we shall publish and repudiate the secret treaties… The question of War and Peace is so clear that I think that I may, without preamble, read the project of a Proclamation to the Peoples of All the Belligerent Countries…’”

“No gestures. And before him, a thousand simple faces looking up in intent adoration”, explained Reed. Lenin proceeded to read the proclamation, and ended with the words:

“The revolution has opened the era of Social Revolution… The labour movement, in the name of peace and Socialism, shall win, and fulfil its destiny…”

Reed commented:

“There was something quiet and powerful in all this, which stirred the souls of men. It was understandable why people believed when Lenin spoke…”[28]

This was the first time that Lenin had appeared or spoken in public for quite some time, having spent almost four months in hiding. What a transformation in the situation! From underground fugitive to becoming leader of the Russian Revolution.

The insurrection had been successful. In the words of Rosa Luxemburg later: “They dared!”[29] They dared and by their actions transformed the words of socialism into deeds. These events would ‘shake the world’ and make Lenin and the Bolsheviks a household name internationally.

The Soviet Congress continued with its revolutionary business. The results in the elections for a new Central Executive Committee or Presidium were announced: sixty-seven Bolsheviks were elected, together with twenty- nine Left SRs, with twenty other seats divided among smaller tendencies, including Maxim Gorky’s group.

Council of People’s Commissars

The newly elected Soviet Executive Committee then appointed a new government – to be called the Council of People’s Commissars – to run the country in the name of the Soviet Republic. The following day it was announced, amid loud and prolonged cheers, that Lenin was chosen, without portfolio, as Chairman of the new government. The list of members of the new government was then read out by Kamenev, who had been newly elected as chairman of the Executive Committee, with bursts of applause after each name. The Left SRs were offered posts in the new government, but for the moment they refused to accept them. The bourgeois concept of ‘Minister’ was rejected in favour of a new, more revolutionary-sounding title of ‘Commissar’.

Trotsky recalled a conversation with Lenin about the new revolutionary terminology to be adopted to describe members of the new government:

“‘What shall we call it?’ asked Lenin, thinking aloud. ‘Only let us not use the word Minister: it is a dull, hackneyed title.’

“‘Perhaps ‘Commissars’’, I suggested, ‘only there are too many Commissars just now. Perhaps Supreme Commissars? … No, ‘Supreme’ sounds wrong too. What about ‘People’s Commissars’?’

“‘People’s Commissars? Well, this sounds alright. And the government as a whole?’

“‘Council of People’s Commissars’, picked up Lenin. ‘That’s splendid; it smells of revolution.’”[30]

Apart from Lenin as Chairman of the Council, other appointments included:

People’s Commissar of the Interior: AI Rykov

Agriculture: VP Milyutin Labour: AG Shlyapnikov

Army and Navy Affairs: A committee consisting of: VA

Ovseyenko (Antonov), NV Krylenko and PY Dybenko

Commerce and Industry: VP Nogin

Education: AV Lunacharsky Finance: II Skvortsov (Stepanov)

Foreign Affairs: LD Bronstein (Trotsky) Justice: GI Oppokov (Lomov) Food: IA Teodorovich

Posts and Telegraph: NP Avilov (Glebov) Chairman for Nationalities’ Affairs: JV Dzhugashvili (Stalin)

The office of People’s Commissar of Railways was left temporarily vacant, mainly as a result of the strained relations with the leadership of the Menshevik-controlled All-Russian Railway Workers’ Union.

The Congress continued with a number of other sessions, accompanied by numerous intervals and breaks. It was, without doubt, a real proletarian revolutionary assembly, the likes of which nobody had ever witnessed before. Power was finally in the hands of the Soviets, in their hands, the hands of the representatives of the proletariat and poor peasants.

Every decision of the Congress was met with enormous enthusiasm, hurrahs, thunderous clapping and caps and hats thrown into the air. The delegates also sang the funeral march in memory of the martyrs of the war, as well as the Internationale. Everyone could sense that the working class was finally in power! This was the most democratic revolution in history.

Morgan Philips Price, Manchester Guardian journalist, was so astonished that he couldn’t believe his eyes. He had never experienced anything like it:

“Soon I was beginning to feel that the whole thing might be a mad adventure. How could committees of workmen and soldiers, even if they had the passive consent of war-weary and land-hungry peasants, succeed against the whole of the technical apparatus of the still-functioning bureaucracy and the agents of the Western Powers? Splendid as was this rebellion of the slaves, as showing that there was still hope and courage in the masses, it was surely doomed in the face of these tremendous odds. Russia could hardly escape the fate of Carthage.”[31]

But deep down, there was a feeling of hope for the future, born out of the horrors of war. “It seemed as if there was, for the first time for many months, a political force in the country that knew what it wanted”, wrote Price: “This was clearly reflected in the common talk in the streets.”[32] “Everything happened so simply and so naturally”, wrote Victor Serge: “It was all quite unlike any of the revolutionary scenes we knew from history.”[33]

History was being made – and the masses felt and participated in it. For the delegates in Smolny, celebrating their victory, their hearts were uplifted, their eyes fixed on the future, while their ears were still ringing with Lenin’s immortal words: “We shall now proceed to construct the socialist order.” With these simple words, Lenin announced the greatest event in history and the beginning of a revolutionary new era internationally.

References

[1] Quoted in Liebman, The Russian revolution, pp. 242-3

[2] Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917, p. 557, emphasis in original

[3] ‘Statement by Kamenev and Zinoviev’, 11 (24) October 1917, The Bolsheviks and the October Revolution: CC Minutes, p. 90, emphasis in original

[4] Lenin, ‘Letter to Comrades’, 17 (30) October 1917, LCW, Vol. 26, pp. 195-6

[5] Ibid., p. 203, emphasis in original

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid., pp. 212-3, emphasis in original

[8] Ibid., p. 213

[9] Lenin, ‘Meeting of the Central Committee of the RSDLP(B)’, 10 (23) October 1917, ibid., pp. 191-2

[10] Ibid., p. 192

[11] The Bolsheviks and the October Revolution: CC Minutes, p. 103

[12] Joseph Stalin, p. 38

[13] Lenin, ‘Letter to Bolshevik Party Members’, 18 (31) October 1917, LCW, Vol. 26, p. 217, emphasis in original

[14] Lenin, ‘Letter to the Central Committee of the RSDLP(B)’, 19 October (1 November) 1917, ibid., p. 223

[15] The Bolsheviks and the October Revolution: CC Minutes, p. 120

[16] Ibid., p. 112

[17] Price, Dispatches From the Revolution, p. 90

[18] Lenin, ‘Letter to Central Committee Members’, 24 October (6 November) 1917, LCW, Vol. 26, p. 235

[19] Sukhanov, The Russian Revolution 1917, p. 620

[20] Ibid.

[21] See Reed, Ten Days that Shook the World

[22] Stalin, Pravda, No. 241, 6 November 1918, The October Revolution, p. 30

[23] Stalin, Pravda, No. 269, 26 November 1924, The October Revolution, p. 72

[24] Price, Dispatches From the Revolution: Russia 1916-18, p. 91

[25] Quoted in Liebman, The Russian Revolution, p. 274

[26] Quoted ibid.

[27] Trotsky, Lenin, pp. 126-7

[28] Reed, Ten Days That Shook the World, pp. 128-9, 132

[29] See Luxemburg, ‘The Russian Revolution’, Rosa Luxemburg Speaks, p. 395

[30] Trotsky, On Lenin, p. 114

[31] Price, Dispatches From the Revolution, p. 94

[32] Ibid.

[33] Quoted in Liebman, The Russian Revolution, p. 285