Today marks 54 years since Bloody Sunday, when soldiers of the British paratroop regiment opened fire on a peaceful civil rights march in the North of Ireland. 13 people were killed immediately, and a 14th victim died later as a result of his injuries. For over half a century, the British state has covered up this atrocity. Last October, one of the soldiers involved in the massacre was acquitted of any responsibility for these crimes. Still to this day not one of the killers has been brought to justice.

On this occasion we republish an article written on the 50th anniversary written by Belfast-based veteran socialist Republican Gerry Ruddy who looks at those events, which formed part of a pattern of brutal oppression by British imperialism, and the reaction and consequences that the massacre provoked; with additional commentary by Ben Curry.

On 30 January 1972, members of the British Army paratroop regiment fired live rounds into a peaceful civil rights march on Rossville Street, in the Bogside area of Derry. By the time the shooting stopped, 13 people lay dead. Through their actions, the British imperialists had poured kerosene onto the flames of the ‘troubles’ into which Ireland was then descending.

It was a crime that shocked the world. Before the dead had even been identified, they were accused of being ‘terrorists’ responsible for their own slaughter. The cover up had begun, and to this day it hasn’t stopped.

But the events of 30 January 1972 were no aberration. Ireland was Britain’s first colony. It was where the British Empire had perfected its methods of colonial rule. From here, it exported these ‘refinements of civilisation’ across one quarter of the Earth’s surface. And by the twentieth century, a corner of Ireland remained as Britain’s last direct colonial possession.

Bloody Sunday in 1972 was only the latest link in a chain of atrocities reaching back to the earliest days of the British Empire. It was not even British imperialism’s first ‘Bloody Sunday’.

Two Bloody Sundays

Both Ireland and India have had much in common. Both were conquered by the British. Both suffered famines in the 19th century. In Ireland, millions starved while food continued to be exported. In India, millions died in two famines in the 1870s and 1890s. The British established work camps, but they were too far from the areas most in need of relief. Despite the advice of Queen Victoria, the Viceroy refused to buy up grain for distribution to the starving, arguing that nothing should be done to interfere with the free market. And in 1943-44, millions perished in the Bengal famine, the worst famine under British rule.

And both countries had their Bloody Sundays.

When the First World War broke out, Nationalists in both Ireland and India were persuaded to encourage recruitment to fight in the ‘Great War’, with the British offering vague promises of self-government in exchange. Over a million Indians and hundreds of thousands of Irish enlisted. Needless to say, they were betrayed.

When the War ended the British Government was determined to hold on to its Empire. It brutally put down the Easter rising in Dublin in 1916, knowing that a successful rising would have inspired other subject nations to resist the Empire. To secure important bases for its own security, it agreed to the partition of Ireland. But the suppression of the Easter Rising had created a backlash. Nationalist Ireland had become increasingly difficult to govern.

A similar situation arose in India. Inspired by the Easter Rising of 1916, many Indians looked forward to their own independence. In the heart of the Punjab region of North West India, in the City of Amritsar, unrest erupted following the arrest of pro-independence leaders Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew and Dr. Satya Pal. The previous month, they had organised two ‘hartals’ or general strikes. The officer in charge of the British forces was the Cork-educated Brigadier General Dyer, who had been sent to the region in 1919 by Sir Michael O’Dwyer, Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab.

Demonstrations were banned. However, one such demonstration was planned for Sunday 13 April 1919, coinciding with a religious festival. The streets were jammed with both demonstrators and pilgrims.

Without warning, the British forces opened fire. For ten minutes, they fired 1,650 rounds into the thickest parts of the crowd. In the end, between 350 and 1,200 Indians lay dead.

Under the martial law applied in the days that followed, the British hung a further 18 people, and flogged many more.

Dyer then ordered that an alley, where a European woman had been seriously assaulted, should be designated a “crawling alley”. All Indians that passed through it would only be allowed to do so by crawling on their stomachs. By such methods did Dyer believe that he had restored order to the British Raj. Yet he was mistaken. Within 30 years, India, although partitioned, was freed from the British Raj.

Just 18 months after the massacre at Amritsar, Ireland had its own ‘Bloody Sunday’. In the morning of Sunday 21 November 1920, the Dublin brigade of the Republican Army killed 14 suspected British Army agents and supporters.

In retaliation for those killings, that afternoon the British Army opened fire on a peaceful GAA match and its spectators, killing 14 and injuring many more.

Later that evening, Dublin IRA leaders Dick McKee and Peadar Clancy, and a civilian named Conor Clune, were taken into custody, brutalised, and then killed by their British captors.

The fight for civil rights

The partition of Ireland had led to the creation of two states: one with a Catholic majority in the South, and the other with a Protestant majority in the North. The birth of the Northern state was accompanied by state-sponsored pogroms of Catholics/Nationalists. The electoral system was fixed to the Unionist advantage by gerrymandering: electoral boundaries were repeatedly redrawn, and even the electoral system itself would be changed to keep a Unionist majority. Unionists implanted sectarianism into the very fabric of the state. For fifty years, Catholics in the Northern Ireland state were an oppressed minority comprising one-third of the population.

When the Civil Rights campaign started, peaceful protests were met with the full force of the state, as the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) batoned marchers, allowed right-wing Unionists to take over towns to prevent civil rights demonstrations from assembling, and unleashed a vicious attack against a student demonstration at Burntollet. The worldwide publicity these events attracted forced the Unionists, under pressure from the British government, to introduce a minimum programme of reforms. The civil rights movement kept up the pressure. They insisted on equal rights for everyone. And they continued to march and agitate.

For nearly three years, there was political upheaval and the mobilisation of underground armies. Loyalists turned to both the UVF and the newly formed UDA for protection, while the IRA began splitting in two due to its unpreparedness to defend Catholic areas that came under attack in 1969. Hence the re-formation of the Provisional and the Official IRAs.

Right-wing Unionists demanded a crackdown, and eventually the local Unionist government, under Brian Faulkner, introduced internment on 9 August 1971. But only nationalists and Republicans found themselves interned. Rather than containing the ‘troubles’, it led to a drastic escalation of violence. Both wings of the IRA escalated their armed activity.

Many working-class Catholic youths had joined both wings of the IRA to defend their communities against the sectarian attacks of the Paisleyites and the RUC; and to fight British imperialism, which tormented them. Many of the most sincere socialist and revolutionary youth joined their ranks. But neither the Officials nor the Provisionals had a clear plan to defeat British imperialism.

The plan of the Provisional IRA to achieve a united Ireland was simple. They believed that through a campaign of bombings designed to impact economic targets, British imperialism would be convinced that it was uneconomical to hold the North of Ireland. But British imperialism calculated otherwise. Centuries of fostering sectarian strife had brought Ireland to the precipice of civil war. To leave the North to its own devices would only mean letting that civil war slip beyond its control. The British calculated that doing so would have far more severe political, commercial and economic implications than the Provo economic campaign could inflict. Better to conduct the civil war on its own terms and beat the Catholics once more into submission.

The Provos now intensified their economic campaign and sadly, as had been predicted by the Officials, there were civilian casualties. Although, it should be noted, the Officials themselves targeted the property of establishment figures, killed Senator Jack Barnhill, and burned property owned by Unionists in Belfast, Derry and Newry.

There was an increase in street marches. Rumours circulated about systemic torture. Marches were banned. However, internment had mobilised the Catholic working class, who were subjected to daily harassment, raids and brutality in the ghettos by the security forces. Moreover, their political representatives had already withdrawn from Stormont in protest at these ‘security measures’.

The Official IRA had strong disagreements with the Provos. In particular, they disagreed with the latter’s economic bombing campaign. When the Provos bombed the Shankhill and killed two people, fighting had erupted between the Catholic and Protestant workers at the Gallagher’s tobacco factory. Then, 15 Catholics were killed in the bombing of McGurks Bar by the UVF, which the Army tried to claim was an IRA “own goal”. In December 1971, the Provos bombed a furniture shop on the Shankill, killing four people including two children.

Seamus Costello, then an Official, had said, “we have no common ground, good, bad or indifferent, with the Provisionals.”[1]

The ‘Officials’ held a position which was called ‘Defence and Retaliation’. But in truth, there was so much ‘defence’ and ‘retaliation’ that it really became, as one volunteer described it, an “unplanned, chaotic armed struggle”. The combination of armed struggle with political struggle, particularly on the streets, was becoming problematic.

When 1972 dawned, the Belfast Telegraph ran the headline, “The IRA is Beginning To Lose The War”.

They could not have been more wrong. The rest of January saw an escalation of violence, particularly in Derry where hundreds of shots were fired at the security forces, and many nail bombs were thrown. Two policemen were killed when their police car was riddled with bullets on 27 January. The violence was widespread. An oil depot in Gamble Street, the Orpheus Inn in York Street, a building on Corporation Street, a garage on Victoria Street, and the Harbour Commissioner’s boat, all in Belfast – all were blown up. Two explosions took place on the perimeter of the Holywood army barracks. The biggest bomb to be found until that point was defused on the border at Silverbridge. Two telephone exchanges were bombed in County Tyrone. 14 bombs were detonated on the Wednesday before the Sunday march. A gun battle, lasting over two hours, took place on the border around Forkhill, in which over a thousand shots were exchanged between the Provisional IRA and the British Army.

A peaceful civil rights march was targeted on Magilligan Strand beside an internment camp, which had opened just three days earlier. The marchers were confronted with barbed wire and 80 members of the Paratroop Regiment, alongside some 50 RUC men, and 80 Green Jackets (a regiment of the British Army). Fifty demonstrators attempted to use the ebbing tide to go around the wire. The paratroops opened fire with gas guns and rubber bullets, and the police and Army then joined in with batons and rifle butts. They fired rubber bullets at close range. The marchers, bloodied and limping, departed. Simon Winchester, who had been observing these events with his family, described it as “the brutal act of an arrogant military”[2]

The following Saturday, there was another civil rights march – this time from Dungannon to Coalisland. It produced “confrontation, rubber bullets, CS gas – many participants huddled in the rain inside the walls of a brickyard, with the angry British Army at the gate.”[3]

It was now obvious, from the behaviour of the Brits, that a change was coming. At a secret security briefing a few days before Bloody Sunday, GOC General Tuzo claimed that the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), which was organising the march, was “the active ally of the IRA”[4]

Many now believe that the British Establishment had made a strategic decision to drive the civil rights movement from the streets. They wanted to take on the IRA, and could not be distracted by the marchers. Some predicted a confrontation. No one predicted murder.

They went to hear speeches

On Sunday 30 January, the marchers gathered. They had come to defy the marching ban, to walk a certain distance, to listen to the speakers, including Bernadette Devlin, Lord Fenner Brockway (an elderly, liberal anti-imperialist), and to “suffer through the usual collection of NICRA people and northern politicians, Hume and Barr and the others.”[5]

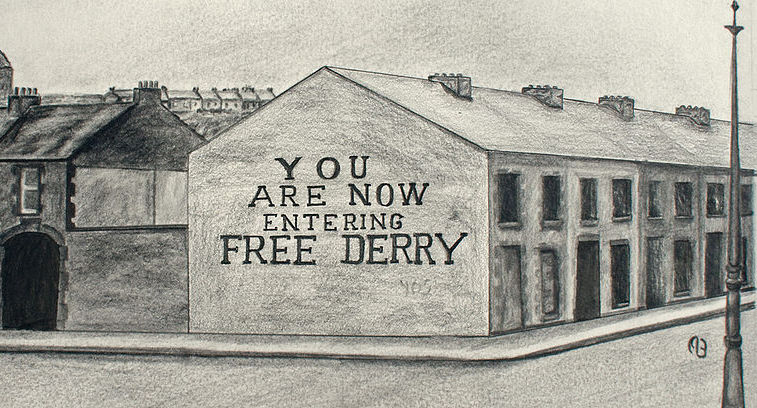

The organisers knew that the Army would not let them leave the Bogside – historically a Catholic ghetto in Derry beyond the city walls – in order to march into what the unionists regarded as “their” city. For decades, they had gerrymandered the city’s electoral wards to ensure a permanent Unionist majority. Housing conditions in the City were appalling for Catholic and Protestant workers alike, and employment opportunities were denied to those considered “disloyal” (i.e. Catholics and Protestant trade unionists).

So the plan was to march up to the barricades behind the sound lorry, and then to withdraw with the lorry to a safe distance from the barricades at Free Derry corner in order to proceed peacefully with speeches. The marchers kept to their plan. They went to hear speeches at Free Derry corner.

A group of so-called ‘Derry Young Hooligans’, as they were customarily referred to at the time, stayed at the barricades to confront the army. There had developed a tradition of rioting – it was almost a ritual for the male teenagers and young men of Derry. As usual, the army responded with rubber bullets, and then drowned the rioters with water cannons, spraying them with purple dye. The situation was contained. Some of the rioters began dispersing. Honour was satisfied.

Even the discredited Widgery Report on the subsequent events admitted, “The army had achieved its main purpose of containing the march and although some rioters were still active in William Street they could have been dispersed without any difficulties.”[6]

Only this time, the Army did not respect ‘tradition’. What the marchers and most of the nationalist politicians did not know was that Sunday 30 January 1972 was the day that the British Army – under the instructions of the British Government, and with the willing support of the then-Unionist government at Stormont – was prepared to open fire on the marchers. They were prepared to use gunfire to drive the nationalist people off the streets for good.

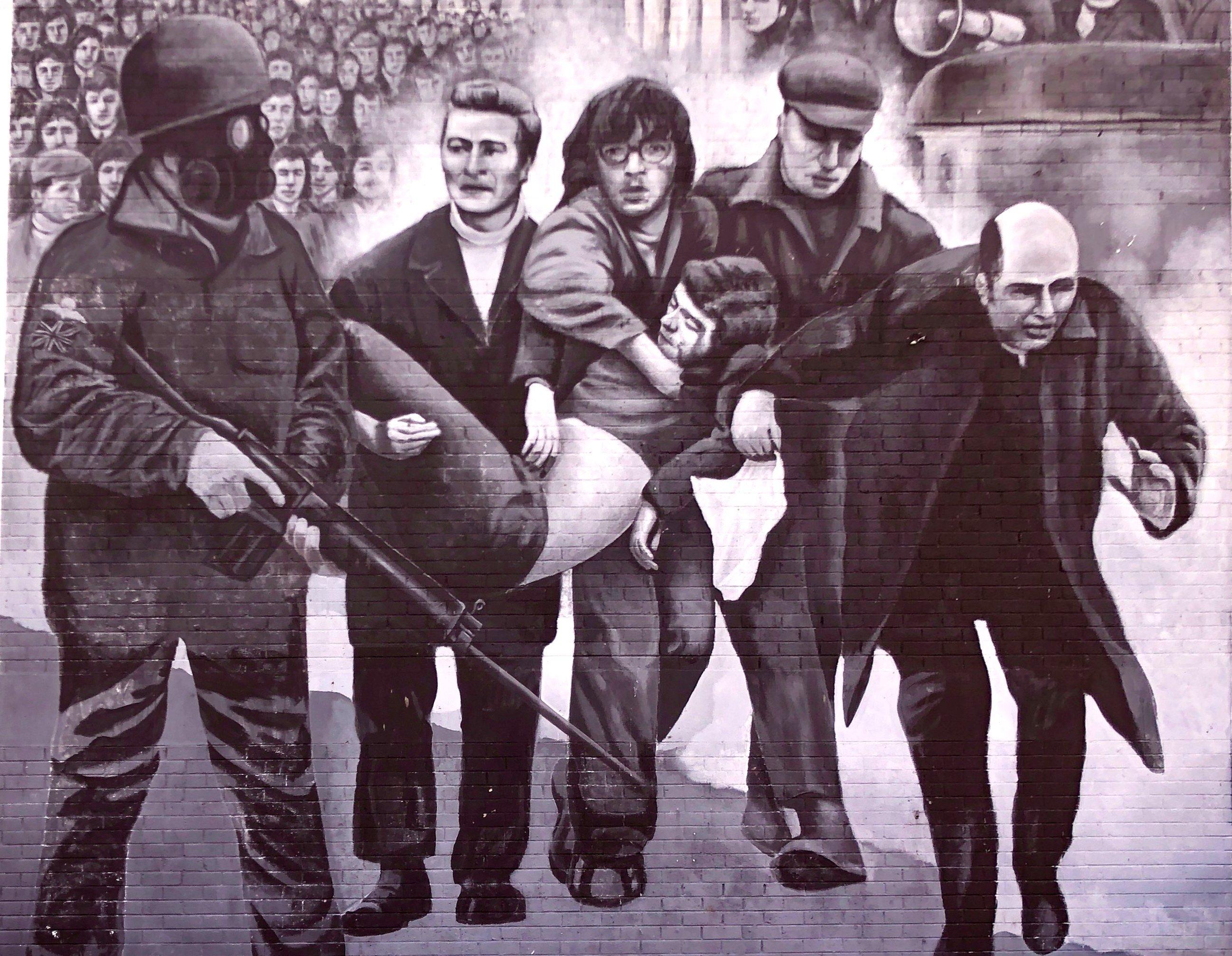

Just after four o’clock in the afternoon, the order was given for the paratroops to go beyond the barricades and sweep up the rioters. For the next 20 minutes, there was bedlam. But amidst the bedlam, it was clear that the British Army had fired 107 high-velocity 7.62 mm shots, not at rioters, but at the mass of people.

They killed thirteen innocent civilians that day, and one man died later from his injuries. 18 people were injured including one woman. Six of the dead were just 17 years old. Not one member of either wing of the IRA was shot. In a vain attempt to justify the shootings, nail bombs were planted on some of the dead bodies. Soldiers had fired into crowds of youths trying to escape into Glenfada Park. Four died. One soldier fired 19 shots into a crowded, built-up area.

The reaction to the killings was predictable. Bernadette Devlin said, “It was mass murder by the British Army.” Taoiseach Jack Lynch said it was, “unbelievably savage and inhuman.” William Whitelaw, a Tory politician, said, “All hell broke loose that day.”

There were three days of rioting outside the British Embassy in Dublin, ending eventually with it being burnt down. Protests and strikes were called, but restricted to mainly Catholic areas in the North. Bernadette Devlin accused Maudling, the Home Secretary, of telling lies, and physically attacked him in the House of Commons!

The response

A member of the IRA summed up the impact of that day:

“Bloody Sunday was a turning point. Whatever lingering chance had existed from change through constitutional means vanished. Recruitment to the IRA rocketed as a result. Events that day probably led more young nationalists to join the Provisionals than any single action by the British.”[7]

Many believed that it was no longer a struggle for civil rights, but a struggle to undo partition. Who could blame the young people who joined the IRA? They were second-class in a sectarian state that despised them. They protested peacefully and they were shot dead for doing so.

Even the moderate nationalist politician, John Hume, said, “Many people down here [the Bogside] feel now it is a United Ireland or nothing.”[8]

Naturally, there was an immediate response from Republicans to the events of Bloody Sunday. Indeed, the Official IRA was first to react on Bloody Sunday itself: two civilians were wounded when the Officials fired a shot at troops using a .303 rifle. Later on, a volunteer fired a revolver, and one volunteer was later wounded.[9]

However, after 4 months of armed struggle, the Official IRA declared a ceasefire on 29 May 1972.

The Provos continued their bombing campaign with disastrous results. They bombed the Abercorn Restaurant in Belfast, injuring 130 people and leaving two sisters legless. A no-warning car bomb in Donegal Street, also in Belfast, killed six and injured over 100 people. Later that summer, the Provos declared a ceasefire and held talks with the British Government in London, in which the Brits took a good look at the future leaders of the IRA: Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness.

The week following Bloody Sunday, there was a huge march in Newry that ended peacefully. That was really the last time that the NICRA brought huge numbers onto the streets. The stage was set for thirty years of conflict, broken by occasional ceasefires, involving many, many deaths.

Seven of the 13 killed on Bloody Sunday were trade unionists. What was the response of the trade union movement? On the day after the massacre, the Executive Committee of Derry Trades Council met in an emergency session. Their statement referred to “the happenings of the previous day in our city.”[10] They then passed a motion of sympathy with the relatives of those murdered, and expressed their hopes that the injured would “soon be restored to health”. And that was it!

Worse was to come. A delegate conference of Northern trade unionists was held to consider its response to the ‘troubles’. There were representatives from the World Confederation of Labour, the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, the World Federation of Labour, the International Labour Organisation, and 110 observers from unions and union congresses around the world. Vic Feather, the General Secretary of the British TUC, and a delegation from the Scottish TUC were also in attendance.

But the only decision of this assembly was to endorse a watery resolution, full of bland homilies, declaring that, if given the necessary financial assistance, the people of Northern Ireland could work together, etc., etc.

There was no condemnation of the killings. There was silence on the demands of the civil rights movement. Not one individual condemned the killings. And there was no reference to the seven murdered trade unionists who were being buried as the conference itself was going on. More importantly, there was no plan of action to respond to this atrocity. When the time came for the trade unions to take action and retaliate, they expressed platitudes.

This should not have come as a surprise to the civil rights marchers. The official trade union movement was utterly reformist, and welcomed collaboration with the state. Indeed, the ATGWU and the GMB tolerated anti-Catholic practices in their branches. There is clear, historical evidence that full-time officials collaborated with the RUC to clear out their own ranks. The Bennett Report in 1979 confirmed details of the savage beating of detainees. Full-time officials would point out Republicans engaged in trade union activity. There was no ambiguity in their support for the RUC. At a meeting between unions and the RUC, the trade unionists present claimed that the Trade Union Campaign Against Repression, a broad front of trade unionists, was a Provisional IRA front. It was not.

Herein lay the tragedy of the entire civil rights movement. Only the struggle of the working class, united under a socialist banner, could have defeated British imperialism. This, the civil rights leadership could not understand. They failed to link the fight for democratic rights for Catholics to the class struggle and the broader fight for the liberation of the whole working class. Meanwhile, the trade unions – the official mass organisations of the working class – were infected with reformism. In the best of circumstances, adaptation to the capitalist state is inherent in reformism. But when that state is built on sectarian division, reformism takes on the same ugly, sectarian features.

When the contradictions in Irish society reached the cusp of civil war, young, working-class Catholics naturally turned towards those who had the guns and the semblance of a plan. But the Provos’ plan was a dead end. There was no place for the masses within it. The spiral of violence only stoked existing sectarian animosity.

In short, the tragedy of the civil rights movement could be summed up as a crisis of leadership.

Politically, for the Unionists who had called for a clampdown on the civil rights movement, Bloody Sunday was a disaster. By the end of March 1972, the British Prime Minister Ted Heath had, for all intents and purposes, abolished Stormont and introduced direct rule. An attempt to re-assemble Stormont with a power-sharing Parliament was brought down by Unionists. It would be nearly thirty years before Unionists would be back in power, albeit having to share that power with Nationalists.

After Bloody Sunday, the Catholic population was almost completely alienated from the Northern state. That sense of alienation was only heightened when the official report into the events of that day was published on 18 April.

On 30 January 1972, before the blood of the victims had dried, Army Captain Michael Jackson arrived at the scene of the recent massacre. He proceeded to interview each paratroop, compiling a list of every shot fired. Not a single shot recorded by Jackson corresponded to those actually fired. The statements that he recorded presented the victims as wielding nail bombs, pistols, rifles and even exchanging fire with the soldiers. In some cases, Jackson recorded trajectories that miraculously passed straight through brick walls before hitting their victims.

Jackson then proceeded to diligently transcribe these testimonies, by hand, for distribution to British embassy staff around the world as the “official” version of events. In the hours after the massacre, British imperialism committed a second crime against its victims: a filthy cover up that involved slandering the dead. The same “shot list” formed the basis of the Widgery Report – the official British version of events for 38 years, which almost completely whitewashed the actions of the British Army. And for his services to the British Empire, Captain Michael Jackson’s career lifted up, high into the stratosphere: he became company commander in 1979; regiment commander in 1984; and Chief of the General Staff of the British Army by 2003 – just in time to lead the British Army on an imperialist adventure in Iraq.

The Troubles

After the introduction of direct rule, the loyalist paramilitaries went on the offensive. They conducted random killings of Catholics, sometimes in the most horrific manner. In truth, none of the organisations or political leaderships emerged from the events of that year with much credit. It was the worst year of all the ‘Troubles’. 496 people died. Civilians suffered the most, with 258 killed – of whom 77 were Protestants and 174 were Catholics. Of the security forces, 15 police officers, including two reserve police; 108 from the British Army; 26 from the Ulster Defence Regiment; as well as 74 Republicans; 11 loyalists, and 9 others were killed.

Bloody Sunday ended the street politics that had mobilised thousands. The people became observers in the ensuing struggle between the various combatants. Only on rare occasions was their participation required. The working class was even more divided than it had been before the ‘troubles’.

Despite the best efforts of many to bring class solidarity into politics in the North, as long as the conflict continued, sectarian polarisation was too strong. Of course, there were minor advances, but the sad fact is that the forces for socialism were weakened, and the working class emerged far more divided than it had been for decades.

Since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, Sinn Féin and the DUP have become the majority representatives of their respective ‘nationalisms’. Neither has proved very competent at governing! Both have accepted the dictates of capitalism, despite Sinn Féin’s so-called ‘revolutionary’ past. They have re-interpreted their past to claim that the armed struggle was necessary to achieve what they call “equality”. The claim came as a surprise to many of the volunteers of the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, who thought they were fighting for a united Ireland!

But even if we accept the idea that the struggle was not at all about a united Ireland but was rather about ‘equality’, we ask: where is that ‘equality’? The Unionist veto remains. The right of self-determination is out of reach. The power to call a border poll rests exclusively with the Tory Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. And in the city of Derry – where the civil rights movement erupted in 1968 and where it was also extinguished in blood in January 1972 – 47% of adults are ‘economically inactive’ and 17.6% have no formal qualifications. These are worse levels than anywhere else in Britain or Ireland. Where is the ‘equality’ here?

The generation that has grown up since the Good Friday Agreement is less concerned with identity and nationalism than it is with the cost of living, education, the soaring rate of inflation, jobs, housing, and the environment. They don’t want paramilitaries, who pose as the macho defenders of their ‘communities’ while condoning, or actually engaging in, the drug trade. Rather, there is a need for political activists in the tradition of James Connolly and the others who followed in his path.

A century has passed since British imperialism’s Bloody Sundays in India in 1919 and in Ireland in 1920. Half a century has now passed since the Bloody Sunday of 30 January 1972. On that day, British imperialism showed itself willing to slaughter those it regarded – at least officially – as its own ‘citizens’, for the crime of exercising the right to peacefully protest.

But these events are not mere history. In every one of its colonial possessions, British imperialism has a litany of similar crimes to answer for. And today, imperialism continues to commit similar atrocities. It was once the boast of British imperialists that the sun never set on their empire. James Connolly made the retort that neither had the blood ever dried on the British Empire.

The task for socialists is to patiently explain the lessons of the past – to learn from the mistakes that were made in decades past, including by socialists and progressive Republicans – and to build a party guided by Marxist ideas, that will provide direction in the struggle for a socialist republic, while always reaching out to all sections of the working class.

To honour the victims of every Bloody Sunday, to prevent further Bloody Sundays, it is necessary to build such an organisation.

Featured image: Sonse, Flickr

[1] page 171 “The Lost Revolution” Hanley &Millar pub. Penguin 2009

[2] page 257 “The Irish Troubles” J Bowyer Bell Pub Gill & MacMillan 1973

[3] ibid.

[4] page 17 Irish News 25/1/22 On This Day Ed. Eamon Phoenix

[5] page 267 “The Irish Troubles”

[6] ibid.

[7] page 151 “Armed Struggle A History of the IRA” Richard English, pub. Macmillan 2003

[8] page 136 “The Troubles” Tim Pat Coogan, pub. Hutchinson 1995

[9] page 174 “The Lost Revolution” Hanley and Millar, pub. Penguin 2009

[10] page 25 “War and an Irish Town” Eamon McCann, pub. Pluto Press 1993 3rd Edit.