One hundred years ago, on 3 May 1921, the partition of Ireland became law in the British parliament. As the Marxist revolutionary, James Connolly, had predicted, partition created “a carnival of reaction both North and South”.

It took years of terror, pogroms and bloodshed to establish what the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, James Craig, termed a “Protestant state for a Protestant people”. In the South, the newly established Free State was baptised in the blood of the Republicans who resisted the Treaty and partition.

“From my point of view it is something obviously to celebrate,” cheerfully opined Boris Johnson, as the centenary of this great crime of British imperialism approached. But British imperialism has little to celebrate.

A century on, the political regime based at Stormont is mired in crisis. After three years in suspension, the Stormont Executive seems to perpetually totter at the brink of collapse. Unionism has lost its majority and its politicians are despised. Then there is the question of Brexit – itself a product of the senile decay of British capitalism – and the status of the North now Britain is out of the EU.

With ever greater insistence, the question of unification and of a border poll is being posed. Yet, since the 1960s, British imperialism has had no interest in holding onto the North of Ireland. The problem is it cannot so easily rid itself of this corner of Ireland either.

It has become a prisoner of its past policies. Having once stirred up sectarianism, it has created a force which has grown out of its control. As long as capitalism exists, the consequences of the barbaric division of Ireland and centuries of inculcating sectarian division can never be undone. Only on the basis of uniting the working class for a revolutionary struggle against capitalism – and with it, partition – can sectarianism be overcome.

A long history of divide and rule

The British ruling class has consciously used sectarian division to rule Ireland for centuries. From the 17th Century, the mass expulsion of Irish Catholics from Ulster, and their replacement by Protestant planters from Scotland and England was intended to provide the British ruling class with a permanent base of support on the island.

But despite the efforts of British imperialism, the poor and downtrodden repeatedly clasped hands across the religious divide in struggle against their common oppressors.

In the 1790s, inspired by the international example of Jacobinism and the French Revolution, thousands of small farmers, landless labourers and artisans – Protestant and Catholic alike – came together in the United Irishmen to expel British imperialism. Protestants provided some of the movement’s outstanding leaders, including Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet.

It was on the back of the crushing of the United Irishmen that landlords in Co. Armagh incited renewed sectarian division between Catholic and Protestant farmers that ended in bloodshed. Out of this violence emerged the Orange Order, a violently bigoted, cross-class organisation designed to defend the ‘Protestant Ascendancy’. The colonial domination of Ireland became bound up with an aristocratic Tory-Orange clique that operated out of Dublin Castle.

The deliberate policies of the British ruling class thereafter kept Ireland in a general state of backwardness. In Belfast, however, circumstances created a thriving linen industry. By the mid-nineteenth century, Belfast had become the linen capital of the world. On the back of the linen industry an important engineering sector developed, and later Belfast emerged as an important shipbuilding centre. By 1911, Harland and Wolff was the biggest shipyard in the United Kingdom.

The city became the centre of Irish industry. At the start of the 20th Century, whilst the city represented just 8.8% of Ireland’s population, 21% of the island’s industrial workers resided there. Almost all of Ireland’s manufactured goods came from Belfast.

In the industrialised North East of Ireland, sectarianism took on a new significance for the local capitalist class and for British imperialism. It became the primary means of forestalling the struggle of the industrial working class.

To divide the workers, Protestants were given the best skilled jobs in the shipyards and engineering sector. In 1911, of 6,809 workers in the shipbuilding industry, only 518 were Catholics. Meanwhile just 11.4% of engineering workers were Catholics, despite making up one third of Belfast’s population, with many factories becoming Protestant-only closed shops. Protestant workers were incited against Catholic workers. In such a way, the average conditions of all the workers could be driven down mercilessly. As Ramsay MacDonald explained:

“In Belfast you get labour conditions the like of which you get in no other town, no other city of equal commercial prosperity from John O’Groats to Land’s End or from the Atlantic to the North Sea. It is maintained by an exceedingly simple device… Whenever there is an attempt to root out sweating in Belfast the Orange big drum is beaten…” (Quoted in Northern Ireland: The Orange State, Michael Farrell)

But however simple the device, it was not infallible. The common interests of the workers continued to reassert themselves. In 1907, under the leadership of the revolutionary trade union leader, Jim Larkin, the super-exploited workers of Belfast united in a mighty dock strike that saw thousands of other workers join in sympathetic action. When the bosses tried to beat the Orange drum around 12th July 1907, the strike remained unbroken. It took the treachery of the British labour leaders to finally undermine it.

In the wake of the First World War and the Russian Revolution of 1917, a new wave of class struggle would sweep up on the shores of Britain and Ireland. In Ireland it led to a revolution that finally broke Britain’s colonial grip. The spectre of Bolshevism would arrive at England’s doorstep, and it struck terror into the hearts of the ruling class.

The Home Rule Crisis

Before the outbreak of the war, storm clouds had already gathered over Ireland. In the first decade of the twentieth century, the Liberals were swept to power – for the last time as it happened – on the back of the political radicalisation of the working class in Britain. After the 1910 election, they were already in decline and only able to govern with the help of the constitutional nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) MPs. In exchange for the support of the IPP, the Liberals promised a Home Rule Act.

Such an act would give Ireland a (relatively toothless) parliament and would devolve certain powers. In truth, it was a modest reform. But it led to a furious reaction from the bourgeoisie in the North and from the British ruling class, as represented by the Tory Party.

The big bourgeoisie in Ireland had always been majority-Unionist. It wasn’t a question of religious affiliation. Rather, they depended upon the markets of the British Empire for their exports, and they depended upon the armed bodies of the British state to defend their property.

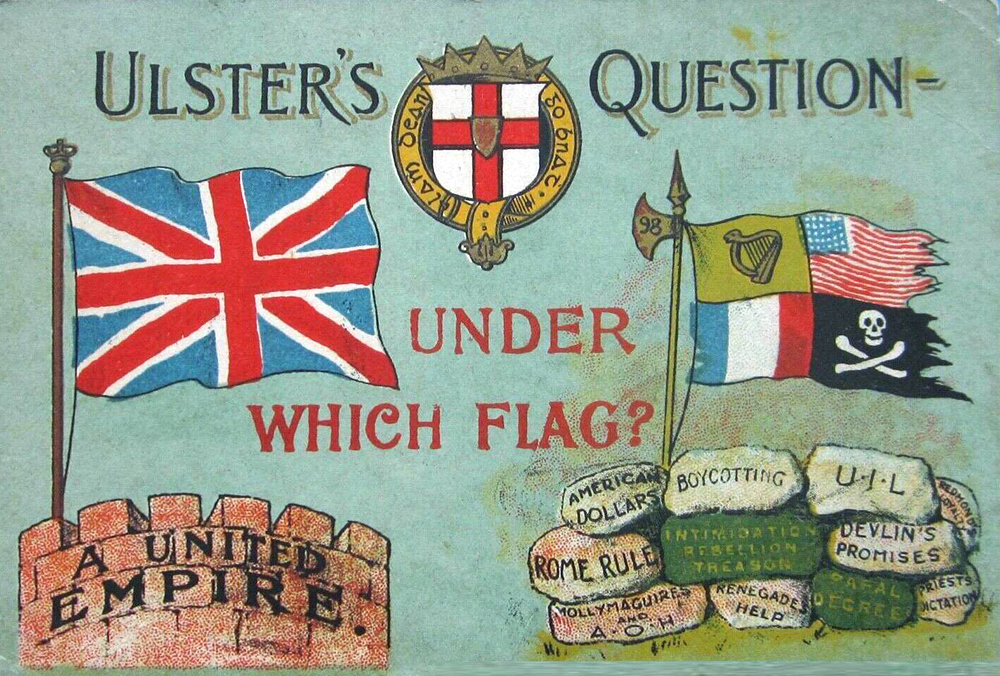

But in Belfast, where there was a Protestant majority, they could beat the Orange drum to try and kill Home Rule in its tracks. In 1912, as the Home Rule Act was being discussed in the British parliament, Lord Carson – with the help of the Ulster Unionist Council representing the Protestant bosses, and with the support of the Tory Party – organised a Unionist militia to stop Home Rule.

The Ulster Volunteer Force was formed, a reactionary body likened by Lenin to the Black Hundreds in Russia. Tens of thousands of the most demoralised lumpen elements of Belfast were armed with 25,000 rifles. Fear was whipped up among the Protestant population of becoming a minority in a Catholic–majority Ireland. “Home Rule is Rome Rule” was the slogan.

British imperialism, represented by the Tories, gave its full support to the Unionist gangs. The imperialist bourgeoisie in Britain, represented by the Tories, understood that introducing Home Rule could encourage similar demands further afield in the Empire.

In Ireland, they could certainly strike a deal with the moderate, constitutional nationalists of the Irish Parliamentary Party. What they feared above all was that modest reforms would whet the appetite of the national movement. Leadership might slip out of the control of the bourgeois moderates, to the revolutionary petty-bourgeois Republicans – or worse – to the socialist-proletarian wing of the movement represented by the great Irish Marxist, James Connolly.

In the face of the arming of the Ulster Volunteers, in March 1914, the hesitant Liberal government finally decided to act. They ordered troops north, but were met by a senior officers’ mutiny at the Curragh military barracks. The government beat a cowardly retreat before this ruling–class rebellion.

Alongside the Home Rule crisis – and as if to confirm the fears of the British ruling class – Dublin erupted in class war. Under the leadership of Larkin and Connolly, the Dublin workers fought a bitter, seven-month class war against the bosses and their attempt to smash the workers’ union with a lockout.

Revolution and counter-revolution in Ireland were growing in step with one another.

Revolution in Ireland

The contradictions in Ireland had arrived at the brink. The outbreak of war in Europe however cut across developments. Before long though, the slaughter, hunger and suffering of the war would prepare a mighty, continent-wide revolutionary backlash.

The first break in the ice was delivered in Ireland with the Easter Rising of 1916. Less than a year later, revolution broke out in Russia, and on 5 November 1917, the dictatorship of the proletariat was established there under the leadership of the Bolsheviks. Shockwaves rebounded throughout Europe. In November 1918, the Kaiser was deposed and workers’ councils sprang up across Germany.

In Ireland too, a revolutionary crisis had matured. The brutal crushing of the Easter Rising in 1916 had crystallised a mood of revulsion towards British imperialism. In April 1918 a massive general strike against conscription rolled across the island. Later in the year a general election saw the surviving leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916 contest seats across Ireland using Sinn Féin as their political vehicle. They took 73 seats, whilst the previously dominant Irish Parliamentary Party was reduced to just six.

The Unionists under Carson took 22, all confined to the North East. Yet in the four Belfast seats that the Unionists took, Labour Representation Committee candidates came second with an average of roughly 25% of the vote. Nothing could be further from the truth than to paint the Protestant workers of the region as one reactionary bloc.

The Labour and trade union leaders allowed Sinn Féin to take the lead. Labour did not contest the election. From then on they played no independent role, accepting the idea of a capitalist independent Ireland.

The election was nevertheless a watershed moment. The grip of the bourgeois, constitutional nationalists over the national movement had been broken. In January 1919, twenty-seven of Sinn Féin’s elected MPs – meeting under clandestine conditions – seceded from Westminster and constituted themselves as Dáil Éirrean, declaring the body the legitimate government of the Republic of 1916. The scattered remnants of the Irish Volunteers were regrouped into an Irish Republican Army, which began a guerrilla campaign against the British. The War of Independence had begun.

But the revolutionary war lacked a clear, revolutionary, working-class leadership. The murder of James Connolly after the Easter Rising had deprived the Irish working class of its most outstanding representative. The second-rank leaders of the Irish Labour Party – the party founded by Connolly – stood aside as the revolutionary tide swept Ireland. The petty-bourgeois leadership of Sinn Féin now at the head of the revolutionary movement thus faced no serious competition.

Despite the petty bourgeois leadership of Sinn Féin – which concentrated on guerrilla methods and the setting up of alternative, mirror institutions to challenge those of the British state such as Dáil Courts – the working class nevertheless formed the backbone of the Irish Revolution.

1919 saw the European-wide wave of revolutions reach its climax. Soviet Republics were formed in Hungary and in Bavaria in southern Germany. A wave of factory occupations brought Italy to the brink of socialist revolution. The tide of the Russian Civil War was turning in favour of the Soviets.

Meanwhile, the workers and small farmers made Ireland completely ungovernable for the British. Everywhere, factories in the towns and creameries in the countryside were occupied. The red flag was hoisted by the workers and they were declared under soviet control. In April 1919, in response to the arrest of IRA members by the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), a general strike was declared in Limerick. The trades council declared the town under soviet control. Where the British tried to move troops and RIC men, they were met by strikes of the railway workers.

Although sceptical of the petty-bourgeois Sinn Féin leadership, the workers of the North were also infected by the revolutionary mood sweeping Ireland. In January 1919, an engineering strike turned into a virtual general strike in Belfast. The trades council converted itself into a Council of Action – a soviet by any other name. In Britain too, Councils of Action were formed nationwide in 1920 in response to the attempt of British imperialism to intervene against the Soviet regime in Russia.

Britain and Ireland both stood at the precipice of a socialist revolution.

But only a clear, socialist programme could have appealed to all workers, including Protestant workers in the North. The Unionist bourgeoisie were terrified of Bolshevism and the potential for a proletarian revolution. They threatened the Protestant workers with a vision of an independent Ireland that was backward, dominated by the petty-bourgeois nationalists and the Catholic Church. Protectionist measures to foster development in the South, they warned, would damage industry in the North. Such an image of an independent, capitalist Ireland had little attraction for Protestant workers.

The only way to undercut this propaganda would have been a class appeal to the Protestant workers, to break them away from the bosses and imperialism, putting the case for a Socialist Republic. But the Sinn Féin leaders could offer no such alternative, whilst the Labour Party leaders had made no effort to seize the lead.

Indeed, the behaviour of Sinn Féin’s leaders only confirmed the fears of Protestant workers. They did nothing to dispel the idea that they would grant the Catholic Church full control over daily life. Indeed, much of the leadership was tinged with a conservative, Catholic nationalism, whilst the party’s left wing had no distinct organisational or programmatic independence. In 1918, Sinn Féin formed an electoral pact with the IPP in the North to challenge the Unionists, brokered by a Catholic Cardinal. These remnants of the IPP that remained active in the North continued their existence under the leadership of the extreme Catholic sectarian, Joe Devlin.

Britain unleashes counter-revolution

These were the circumstances that British imperialism faced in 1920 and which informed its decision to partition Ireland. By 1920, despite instigating terror across Ireland using the RIC and the hated ‘Black and Tans’, British imperialism had lost control of the majority of the island.

By whipping up sectarian mayhem however, they might be able to hold onto some of the Protestant-majority counties in the North East. Through partition they could retain the most economically developed part of Ireland and a military-strategic foothold.

Throughout these years, they were driven above all by a fear of Bolshevism. Partitioning out a Protestant-dominated quarter of Ireland, creating a statelet based on religious division would, as they saw it, create a permanent, reactionary bulwark against revolution. The question of how to approach partition could also be used to divide Sinn Féin and the IRA.

The question was: where to partition the island? Of the nine counties of Ulster, only four had Protestant majorities. A four-county statelet restricted to the environs of Belfast was deemed by the British government and the Unionists alike as economically unviable. As such, the proposal of the Government of Ireland Act, drafted by Lloyd George in 1920, created two statelets: ‘Southern Ireland’ consisting of 26 counties, and ‘Northern Ireland’ consisting of six.

The plan would include the counties of Fermanagh and Tyrone in Northern Ireland, despite both having large Catholic majorities, simply to give the new entity something approaching viability. The wishes of those living in the region didn’t enter their calculations. Within and close to the borders of the new statelet, the towns of Newry and Derry, both with large Catholic majorities, were also included.

When local elections in January 1920 gave a majority for nationalists in Derry City and the latter declared in favour of the Dáil, British imperialism showed the Catholics by what means they were to be kept in the union. When riots broke out in the city in April and May of that year, the RIC fired directly into crowds of Catholics.

Following new elections in June, the UVF in Derry took to stopping pedestrians and asking their religion. If they were Catholics they were summarily shot. Wherever RIC men were killed by the IRA, the UVF responded with indiscriminate reprisals against Catholics.

In the summer of 1920, on the occasion of the Orange marching season, Edward Carson gave a 12 July speech to signal that this indiscriminate terror was to become a systematic, region-wide policy:

“We must proclaim today clearly that, come what will and be the consequences what they may, we in Ulster will tolerate no Sinn Fein – no Sinn Fein organisation, no Sinn Fein methods … But we tell you [the government] this – that if, having offered you our help, you are yourselves unable to protect us from the machinations of Sinn Fein, and you won’t take our help; well then, we tell you that we will take the matter into our own hands.”

He picked out socialists in particular for pitting Protestant against Protestant:

“… these men who come forward posing as the friends of labour care no more about labour than does the man in the moon. Their real object, and the real insidious nature of their propaganda, is that they mislead and bring about disunity amongst our own people…” (Quoted in Farrell)

In the ensuing wave of violence, Catholics were expelled en masse from the shipyards, engineering works, building firms and linen mills. In the massive pogroms against Catholic workers, the bosses took their revenge against socialists and trade unionists from Protestant backgrounds too.

Labour councillor for Belfast Shankill, Sam Kyle, was expelled from his workplace. So too was Charles McKay, who had been chairman of the engineers’ strike committee in 1919. The former master of an Orange Lodge, John Hanna, was expelled for having worked with Larkin in the 1907 strike.

In total, between the summers of 1920 and 1922, 11,000 workers in Belfast were expelled from their workplaces – out of a population of just 93,000 Catholics. This amidst a terrible post-war depression in which unemployment ballooned.

In August 1920, a wave of violence in the town of Lisburn saw the entire Catholic population forced to flee. The London Daily News described that one summer as “five weeks of ruthless persecution by boycott, fire, plunder and assault, culminating in a week’s wholesale violence, probably unmatched outside the area of Russian or Polish pogroms.” (Quoted in Farrell)

At summer’s end, the British imperialists made the pogromists an official arm of the state by establishing a Special Constabulary. The UVF was absorbed as a part-time armed wing of the state, retaining their old organisation structures as the notorious B Specials. Along with the Royal Ulster Constabulary, they would form a permanent cudgel over the heads of Catholics for the next 50 years. In total, the Specials numbered 40,000 men, paid for and armed by the British state.

A sectarian state is born

As the Government of Ireland Act came into law in May 1921, Tory Minister Sir James Craig resigned from the British government and took up the leadership of the Unionist Party from Carson.

After new elections on 14 May – conducted in an atmosphere of terror against Catholics and socialists – a majority was returned for the Unionists. Craig was made the first Prime Minister of ‘Northern Ireland’. There was no doubting the class character of the regime: the list of Craig’s ministers read like an index of the major capitalists in the North.

In the summer of 1921, negotiations began between the British government and the IRA, which would end in betrayal with a section of the IRA leadership signing the Anglo-Irish Treaty and recognising partition. But the horrors didn’t abate in the North.

Indeed, to prove to the Catholic population that partition was an unyielding fact, the pogroms and violence were intensified. State terror now rained down furiously on the heads of the Catholics with the full backing of British imperialism. By the summer of 1922, 450 people had been killed in violent pogroms, thousands driven from their jobs, and 23,000 people – a quarter of Belfast’s Catholic residents – had been driven from their homes. Unspeakable acts could be listed at will.

The bosses in the North began forming their regime based on permanent subjugation of the Catholic minority – who constituted a third of the population in the six counties.

On 15 March 1922 the parliament in the North passed the Special Powers Bill, which in the words of Farrell, “provided for search, arrest and detention without warrent; flogging and death penalty for arms and explosives offences; and the total suspension of civil liberties.” (ibid. p50)

In July 1922, proportional representation was abolished and new constituencies drawn that were gerrymandered to an astonishing extent. In 1920, nationalists had control of 25 out of 80 councils. By the 1924 elections, they were reduced to control of just two. In Derry, which had a two-third Catholic population majority, a Unionist majority was returned. As the Catholic population increased, threatening to overturn that majority, it was simply gerrymandered again in 1936.

When the 1945 Labour government at Westminster abolished the restricted franchise, it was retained in the North of Ireland, along with the ‘company vote’ – where the directors of rate-paying companies could cast up to six votes. The subversion of any pretence to democracy was quite flagrant. In the words of Major L.E. Curran, the Chief Whip in 1946:

“The best way to prevent the overthrow of the government by people who had no stake in the country and had not the welfare of the people of Ulster at heart was to disenfranchise them.” (Quoted in Farrell)

Alongside all of this, the Unionist Party developed a whole web of patronage. On top of the skilled jobs in industry, control of government brought thousands of white-collar civil service jobs, which were allocated on the basis of religious affiliation. Down to the 1960s a typical local advertisement might read, “Protestant girl wanted as secretary”. Local government – gerrymandered to give a Unionist majority – likewise controlled housing and infrastructure, which was diverted away from Catholics who were allowed to live in squalor.

Counter-revolution in the South

Counter-revolution in the North was supplemented by counter-revolution in the South.

The so-called ‘national bourgeoisie’ in Ireland were only to a secondary extent interested in national liberation. Their primary concern was neither national independence nor the plight of the Catholics in the North. Fundamentally, they were interested in making money. If restoring profits came at the price of only dominating a reduced 26-county statelet rather than all 32 counties, then so be it. Above all, they needed order, peace, and tranquil relations with British imperialism.

Whilst there was a left wing in Sinn Féin and the IRA – as there has always been in Republicanism – there was also a clearly right-wing, bourgeois trend that took up this demand for ‘Order’. British imperialism could arrive at a deal with these people. This trend had reasserted itself time and again in the Revolutionary War, moderating and holding back the workers and poor farmers. Where the workers took over factories or left-wing IRA commanders distributed land to the farmers, the Dáil Courts, with the assent of senior Sinn Féin leaders, often returned the property to its former owners.

In December 1921, this right wing – in the persons of the Dáil’s negotiators, Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith – arrived at an agreement with British imperialism. The Anglo-Irish Treaty accepted the fact of partition, and in return the British conceded a ‘Free State’ in the South, which would continue to swear its loyalty to the British Crown.

The IRA soon split into pro and anti-Treaty factions, with the best left-wing elements of the IRA coming out against the Treaty. Civil war erupted. But the anti-Treaty forces lacked a clear programme able to appeal to the masses, who were at any rate exhausted. Meanwhile, the pro-Treaty Free State forces enjoyed the support of British imperialism and British weapons, which were now directed at the Republicans. Initiative lay with the counter-revolution. The British government put pressure on the Free State to deal with the anti-Treaty IRA – who continued activity in the North – as a condition of the Treaty itself.

The forces of the Free State now set to work at consummating the counter-revolution in the South with the utmost brutality. In the course of the Civil War, 81 anti-Treaty Republicans were executed by the Free State, more than were executed by the British in the entire War of Independence.

The triumph of counter-revolution in the South, connected to the triumph of counter-revolution in the North, led to the formation of an equally reactionary semi-theocratic state. The Free State lived up precisely to the caricature that Unionists had used to scare Protestant workers.

Despite the outward appearance of animosity, counter-revolution in the North and South buttressed one another.

In the North a cruel and elaborate array of methods were used to divide the working class. But despite this, against all odds, within a decade the common interests of the workers reasserted themselves.

In the 1930s, as the Great Depression drove up unemployment, the Unionist state offered next to nothing in terms of relief – to Catholic or Protestant workers. In autumn 1932, rioting erupted in Belfast. Tens of thousands of workers fought pitched battles against the police. As Catholics rioted on the Falls Road, working-class Protestants on the Shankill dug trenches and pitched up barricades in order to draw the RUC away from the Catholic neighbourhoods.

In the South too, in the late 1920s and early 1930s there was a revival of class struggle, with widespread strikes, and bitter struggles on the land against the annuities that the Free State continued to extract from the small farmers to compensate the former British landlords.

The working class, like Antaeus the giant of Greek mythology, despite being repeatedly thrown to the ground, each time rose up stronger than before.

A lasting legacy

This crime of British imperialism has left a lasting legacy of sectarian division that persists to the present day. In 1921 partition served their interests, but it was a short-sighted move that has created a web of contradictions from which British imperialism is at a loss to extricate itself.

At least since the 1960s, British imperialism has had no direct economic or strategic interest in holding onto the North of Ireland and maintaining the regime it created there. However, its divide and rule policies over centuries have created a Frankenstein’s monster. Having whipped up Protestant sectarianism, the latter has taken on a life of its own.

Whilst partition was intended to forestall revolution, the injustices that it engendered have pushed one generation of Catholic youth after another down the road of revolution. In the late 1960s this revolutionary anger exploded in a mass movement for civil rights for Catholics.

But the movement immediately drove into a head-on collision with Protestant sectarianism. Gangs whipped up by Ian Paisley – that were beyond the control of the official Unionist establishment – met the movement with violence and provocations. These gangs didn’t hesitate in pushing the North towards civil war. British imperialism was forced to intervene, embroiling itself in the spiral of reactionary violence of The Troubles.

Today it has become abundantly clear that the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) has done nothing other than place a sticking plaster over these old wounds. After a further fifty years, the degeneration of British capitalism has reached new depths. Brexit and the takeover of the Tory Party by Little Englander nationalists are its political consequences. This in turn has ripped away the sticking plaster of the GFA.

Unionism too is in a desperate crisis. The decline of industry in the North of Ireland has meant that the Unionist bourgeoisie has little to offer Protestant workers. The traditional party of the Unionist bourgeoisie, the UUP, has been smashed and replaced by the DUP, the party of the fundamentalist preacher, Ian Paisley. The old tradition of patronage persists today in the form of the DUP’s nepotism and corruption.

It too is now in crisis. These parties have nothing to offer Protestant workers. All they have left to bolster their support is heightened sectarianism. Meanwhile, loyalist paramilitaries who have remained active ever since the GFA, have become increasingly active over the Irish sea border, attempting to mobilise alienated Protestant youth in sectarian riots.

The clouds of sectarian barbarism, the product of British imperialism, continue to hang threateningly over Ireland. It is vital to learn the lessons of the past, and above all the lessons of the Irish Revolution and of partition. One century ago, the question was sharply posed in Ireland: socialism or sectarian barbarism? Only a bold revolutionary leadership of the working class could have offered a perspective capable of appealing to workers in Catholic and Protestant communities alike. This was lacking and the working class paid a heavy price.

Today, the same question is being posed by history, only with greater insistence.