On 14 August 1969, British troops were deployed onto the streets of the North of Ireland. Operation Banner had begun. At the time, some mistakenly believed they were there to bring peace. The Marxists warned they would bring no such thing. Below we republish an article first printed in the In Defence of Marxism magazine (the theorethical journal of the Revolutionary Communist International) in 2019, marking the 50th anniversary of the British Army’s deployment to Ireland.

Fifty years ago, on 14 August 1969, British troops were sent into the North of Ireland. At first, they were generally welcomed by Catholics as a buffer against the threat of a pogrom. Very quickly the mood changed as the real nature of the British army’s presence made itself felt. It was marked by harassment, housebreaking raids, internment without trial, shoot-to-kill, massacres, and general brutality and discrimination towards Irish Catholics.

The initial, naive response of working-class Catholics in welcoming their presence was wholly understandable. A clear-sighted leadership worthy of the name might have risen above the temporary mood and forewarned of the real significance of events. The British troops were not there to defend Catholics.

But not only did the Civil Rights leaders welcome the presence of the British troops, so too did many self-described “Marxists” in Ireland and Britain. In no time at all, many of these groups – like the SWP in Britain – would make an about-turn and become the most uncritical cheerleaders of the “armed struggle” of the Provisional IRA (PIRA or “Provos”). The Marxist tendency, Militant, led by Ted Grant kept a clean banner and warned about the real role of the British army.

Unfortunately, the lack of a clear-sighted, Marxist leadership in the course of the Civil Rights movement ultimately meant a revolutionary opportunity was let slip in the years 1968 and 1969. It is necessary, if the forces of Marxism in Ireland are to regroup, that the lessons of these events are studied. This is the only way that the movement can be theoretically rearmed in preparation for the new revolutionary wave which impends in Ireland.

An incomplete revolution

In 1968, a social explosion erupted in the North of Ireland around the question of civil rights for Catholics. For centuries the Catholics of Ireland had been subjected to discrimination and persecution. It was in Ireland that the British Empire first perfected its tactic of “divide and rule”.

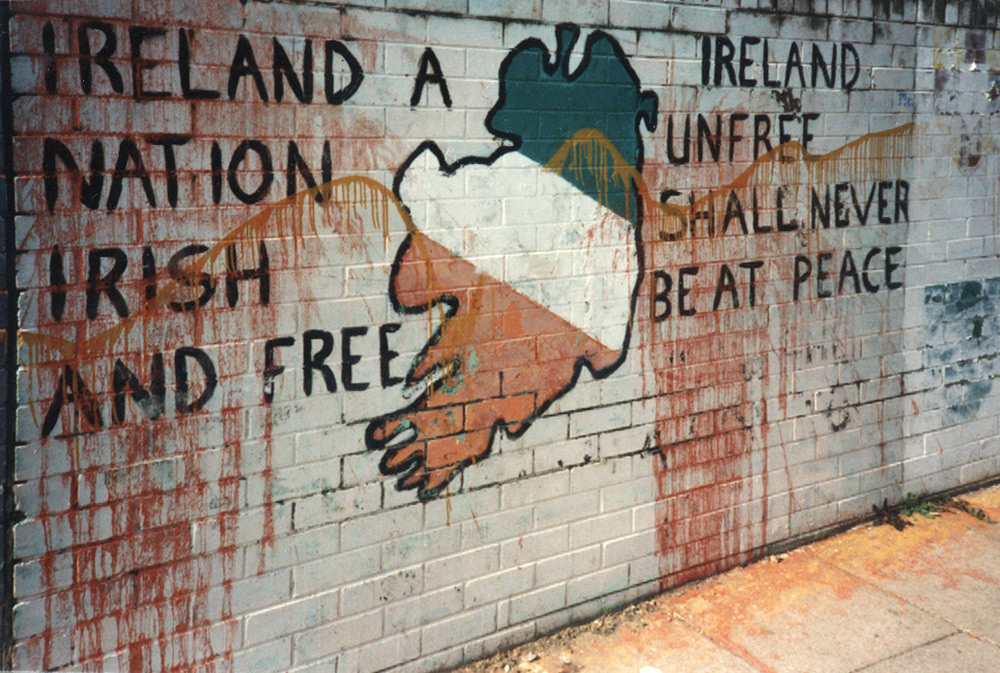

But when revolution swept Ireland from 1919 to 1922, and the British could no longer hold onto the country, they resolved to carve the living body of Ireland in two. Under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, which concluded the revolutionary Irish War of Independence, the South became nominally independent. The same Treaty, however, left the North in the hands of British imperialism.

There were a number of reasons that the British ruling class went down the road of partitioning Ireland, from the purely economic (the region represented 80% of the industrial output of the island); to the military-strategic (Ireland represented an important defensive position on Britain’s West flank). But surpassing all of these considerations was the fear of Bolshevism.

Whilst the Irish Labour leaders had abdicated leadership of the Irish Revolution to the petty-bourgeois nationalists of Sinn Féin, the revolution was nevertheless accompanied by the formation of soviets, factory occupations and attempts by small farmers to redivide the land.

But in 1922, the servile bourgeois nationalists in Ireland proved their completely reactionary character. In the Treaty with England, they agreed to partition Ireland. They would get what they wanted: free rein to exploit the Irish workers in two thirds of Ireland. Meanwhile, the British would retain six counties in the North East.

As Connolly had predicted, partition “would mean a carnival of reaction both North and South, would set back the wheels of progress, would destroy the oncoming unity of the Irish Labour movement and paralyse all advanced movements whilst it endured.” This was exactly what the British ruling class had aimed at.

A regime of reaction

Centuries of carefully cultivated animosities between Protestants and Catholics were whipped up into an orgy of violence. Catholics, socialists and trade unionists were driven out of workplaces. In cities like Belfast, Catholics were terrorised into ghettos.

The sectarian state in the North was engineered as a “Protestant parliament for a Protestant people”. In other words, it was to be a permanent bulwark against revolution and class struggle. The Catholics were to be kept permanently under the boot, and the loyalty of the Protestants was to be maintained by marginally better living conditions, and fear of what would happen if “they”, the Catholics, got the upper hand. Sectarianism was coded into the DNA of the statelet from its inception. The maintenance of such a regime required the creation of a huge apparatus of repression on the one side and of patronage on the other.

Through organisations like the Orange Order, the permanent domination of the Ulster Unionist Party was to be guaranteed. Electoral boundaries were rigged against Catholics; businesses were given extra votes through property; and all positions of importance in the civil service were given to Protestants. Active discrimination in housing and jobs was used to sow the illusion of common interests between Protestant workers and bosses.

And the armed Ulster Volunteers, which Lenin had likened to the Black Hundreds in Russia, were integrated into the state as the B Specials. The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and the B Specials were a permanent, menacing cudgel over the heads of Catholics.

Counter-revolution was not limited to the North. In the South too, partition meant a “carnival of reaction”. The Treaty plunged the South into civil war. The Irish bourgeoisie now established themselves firmly in the saddle. The regime in Dublin, no less than the regime at Stormont, rested on repression and social reaction. The Catholic Church exercised a spiritual and temporal dictatorship, and was given complete control over education, healthcare and all spheres of social life. Even today new revelations about the horrors it inflicted on women and children, in particular, continue to come to light.

The ugly features of such a regime could only repulse Protestant workers of the North. As long as in the minds of Protestant workers a “United Ireland” only meant the absorption of the North into the capitalist South, they were never going to accept such an outcome. It meant joining an economically stagnant, theocratic regime in which Protestants were to become the persecuted minority. And Protestants knew what it meant to be a persecuted minority; they could feel it in the seething discontent of their Catholic neighbours. Uniting Ireland on a capitalist basis only promised to switch the pluses and minuses. As is often the case, the reactionary regimes North and South, which were apparently at loggerheads, in reality, rested on each other across the border.

Such were the bitter fruits of the betrayal of the struggle for independence by the bourgeois nationalists, and the failure of the Labour leadership to place itself at the head of this struggle.

Towards reform

The British had installed at Stormont a regime that was meant to guarantee permanent reaction, permanent sectarian animosity and permanent British domination. But the laws of dialectics dictate that nothing is permanent and everything must change. No one at the 1922 Anglo-Irish negotiations had asked, “What if this settlement no longer suits our interests?”

The needs and interests of British imperialism didn’t stand still. Silent, unassuming changes were undermining the material basis of the Northern statelet. But it is precisely because institutions, ideas and the web of social relations develop according to their own laws, without reference to the needs of society or of this or that class in society, that such change necessitates clashes, crises, catastrophes and revolutions.

By the post-War period, a process of decline began to accelerate. Jobs in shipbuilding, linen and other important industries were being shed across the North. No longer did it hold the same economic importance that it once had. Furthermore, with the invention of nuclear weapons, the island could hardly be said to hold the same strategic value it once had.

Relations with the South had begun to warm by the 1950s, and Britain and Ireland were doing good business. In fact, the South was completely economically dependent on Britain. The sectarian set up in the North only added friction to this relationship. And far from being a bulwark against revolution, the injustices it engendered threatened to become combustible material for a new social explosion.

British imperialism looked therefore toward reform. If possible the ruling class would undoubtedly have opted for immediate reunification but that was ruled out. It is a fact that for 75 years, British imperialism has had no interest in maintaining its grip on Northern Ireland. If it has been unable to release that grip, it is because it has become enmeshed in a web of contradictions of its own making.

This turn in the interests of British imperialism was reflected in the reformist politics of Terence O’Neill, who succeeded Brookeborough as Prime Minister of Northern Ireland in 1963. O’Neill made a string of promises about reforms, and under his premiership, relations with the South began to thaw. In 1965, O’Neill even played host to the South’s Taoiseach (Prime Minister), Seán Lemass. This was an unprecedented step.

But O’Neill’s reforms remained entirely verbal. They did little to satisfy Catholic workers and youth. Meanwhile, they only served to irritate the hardliners in his own Unionist camp. In the early stages of many revolutions, the storm ahead is heralded not by an explosion from below but by splits at the top. Within the Unionist Party, splits began emerging. A right wing around one of O’Neill’s ministers, William Craig, argued vociferously for an end to the “carrot” policy and a return to the “stick”.

More ominously, outside and completely out of control of the Unionist establishment was the party of Ian Paisley. In his insane sermons, this fundamentalist, rabble-rousing preacher accused O’Neill of “bowing the knee to popery” and playing into an (entirely imagined) Catholic Church plot to unite Ireland. The ruling class were learning a lesson. It was impossible to drip-feed sectarian prejudice, to maintain a permanent armed sectarian mob (the RUC and B Specials), and to sow anti-Catholic feeling for decades and then expect to be able to turn the tap off once it was no longer called for.

The reactionary Paisleyite mobs were the product of centuries of sectarian incitement. With the first hint of a change of course these mad reactionaries, of course, cried, “Betrayal!”

O’Neill’s own rhetoric went nowhere as it was on the Unionist establishment that his regime rested. However much he might have liked to have blunted its edges, O’Neill was part and parcel of a sectarian order he could never succeed in disassembling. In his own words, O’Neill explained:

“The basic fear of Protestants in Northern Ireland is that they will be outbred by Roman Catholics. It is as simple as that. It is frightfully hard to explain to a Protestant that if you give Roman Catholics a good house they will live like Protestants, because they will see their neighbours with cars and television sets. They will refuse to have eighteen children, but if the Roman Catholic is jobless and lives in a most ghastly hovel, he will rear eighteen children on national assistance.

“It is impossible to explain this to a militant Protestant, because he is so keen to deny civil rights to his Roman Catholic neighbours. He cannot understand, in fact, that if you treat Roman Catholics with due consideration and kindness they will live like Protestants, in spite of the authoritative nature of their church.”

Civil Rights

In the late 1960s a revolutionary mood was sweeping the world. A wave of successful revolutions had challenged capitalism and landlordism in a number of former colonial countries. Italy, Pakistan, Mexico, Czechoslovakia and of course France were all swept by revolutionary developments in 1968-69. Even in the belly of the beast, discontent was spreading. Rising opposition to the Vietnam war and a mass movement of Civil Rights agitation by the black population swept the United States.

These events reached their peak with the revolutionary events of May 1968 in France, when 10 million workers brought the de Gaulle regime to its knees. These events had a profound impact on the most advanced workers and youth in Ireland too. This was especially the case among the Catholic youth in the North who were burning with indignation at their lack of basic rights.

Left-wing youth in Derry, around the Labour Party Young Socialists, joined left-wing Republicans in organising the Derry Housing Action Committee in 1968 and began organising mass protests. Hundreds of angry workers and youth shut down the meetings of the Derry Corporation. At Queens University in Belfast, a layer of left-wing students were also organising.

And in 1967, to bring together the struggles against the gross inequalities between Catholics and Protestants, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) was formed. Their demands were quite moderate. They were in favour of “one man, one vote” (i.e. ending the business vote); an end to gerrymandering; disbanding the B Specials; an end to discrimination in government jobs; and an end to discrimination in housing.

The allocation of housing and jobs were particularly burning issues. In Northern Ireland unemployment in the 1950s and 1960s stood at about 8%, while in Britain it was an average of 1.5%. But in Derry, unemployment among Catholic men was as high as 30%. The legacy of the divisions that sectarianism had introduced into the working class was that wages remained at just 80% of the level of workers in Britain.

When it came to housing, the Unionist regime, concerned first and foremost with maintaining a Protestant majority, weren’t about to build more houses and upset the demographic balance. Catholic workers could squeeze into more and more densely populated and deplorable slums, or else take the one option always left open to them by British imperialism: emigration. A hundred thousand youths took this option in the 1950s.

None of this is to say that poverty, unemployment and deplorable housing were not features of working-class, Protestant neighbourhoods too. Time and again, the conditions of Protestant workers had forced them to take the road of struggle. The revolutionary traditions of the working class in the North of Ireland are as much the property of Protestant as of Catholic workers: from the 1907 Belfast dock strike, when even the police mutinied; to the 1919 engineering strike, when the workers of Belfast had power within their grasp; to the 1932 Outdoor Relief riots, when Protestant and Catholic workers jointly fought the sectarian state.

But as bare averages, conditions on almost all indices were worse across the board for Catholics. Some of the events which lead up to the first Civil Rights marches typified the discrimination that Catholics suffered. In the first half of 1968 working-class, Catholic families in Co Tyrone, fed up with being constantly refused housing through official discrimination, began squatting newly built homes. One couple with children, who were living with the mother’s parents and six brothers in deplorable conditions, took things into their own hands and occupied one such empty house. But shortly after the family were brutally evicted. The door was broken down with a sledgehammer, and they were physically dragged from the premises. And yet the house just next door was allocated to a 19-year-old, single, Protestant girl without dependents who happened to be the secretary of a local, Unionist politician.

This particular eviction, before the eyes of the media, became a cause célèbre for the Civil Rights movement. On 24 August 1968, the first major Civil Rights march set off from Coalisland to Dungannon in Co Tyrone.

Two thousand marchers set off, but when they arrived at the outskirts of Dungannon, they received a foretaste of what was to come. At the edge of the town, the marchers were turned away by the RUC. A small Paisleyite counter-demonstration had taken up occupancy of the centre of the town. A hardcore of loyalist followers of the Rev. Ian Paisley were determined to stop the Civil Rights movement in its tracks.

Stalinism

It should be noted that on this and other Civil Rights marches, the official leadership of the Civil Rights movement – represented by the NICRA – “led” from behind. Only with great reluctance did they place themselves at the head of the marches. This was principally to prevent the movement from slipping out of their control to the left!

In Derry, which was at the heart of the Civil Rights movement in its early days, it was the left-wing Derry Labour Party and the Young Socialists, which took the initiative and played a leading role in the movement. A leading role was played by self-avowed Marxists like Eamonn McCann. In Belfast, it was People’s Democracy, an amorphous left-wing group that was formed by radical students in late 1968, which took the lead.

The NICRA leadership contained various stripes of opinion from liberals to nationalists, communists and others. However, its main influence came from the so-called Communist Party, which advocated a Stalinist “two-stage theory”.

According to this theory, it was necessary to deal first with the “democratic” question of equality for Catholics. This, it was alleged, was necessary to give the movement the broadest possible appeal. Only then, once real democratic equality had been won, could the question of socialism be posed.

But however “feasible” such a moderate programme appeared, the fact that it did not challenge capitalism would become an enormous obstacle in the unity between Catholic and Protestant workers. After all, if you say, “more jobs for Catholics”, “more houses for Catholics”, unless you also talk about increasing the absolute number of jobs and houses, such slogans can sound a lot like, “less jobs for Protestants”, “less houses for Protestants”. As Eamonn McCann explained in his recollections of this period:

“There was one sense in which the civil rights movement was ‘anti-Protestant’. The movement was demanding an end to discrimination. Its leading moderate spokesmen such as John Hume and Gerry Fitt, insisted endlessly that this was all they were demanding. In a situation in which Protestant workers had more than their ‘fair’ share of jobs, houses and voting power the demand for an end to discrimination was a demand that Catholics should get more jobs, houses and voting power than they had at present – and Protestants less. This simple calculation seemed to occur to very few leading civil rights ‘moderates’, but five minutes talking with a Paisleyite counter-demonstrator in 1968 or 1969 would have left one in no doubt that it was not missed by the Protestant working class.” (War and an Irish Town, p297)

It is in the very nature of capitalism to create artificial scarcity. To allay the potential fears of Protestant workers it would have been necessary for the Civil Rights leaders to offer something more: to offer a socialist programme that could eliminate joblessness altogether and build decent houses for all. This would have been the only way to isolate Paisley and his gangsters. Gregory Campbell, a sectarian who became a prominent member of the DUP in the Derry area (and who today sits as one of the DUP’s ten MPs), in his recollections, expressed feelings that were undoubtedly reflective of more backward layers of Protestant workers that came under the influence of Paisley:

“The thing that pushed me into politics was the whole civil rights scenario […] I saw the nationalists were campaigning for better living conditions, jobs, voting rights, and yet everything they were campaigning for, I couldn’t get either. I hadn’t got running water, I had to go outside to the toilet. I had all the disadvantages that the urban Catholic had, and yet they were campaigning as if it were an exclusive prerogative of Catholics to be discriminated against. I felt the exact same way […] but there continued to be an attitude on their part that they were the only ones discriminated against and I was part of the group that was discriminating against them.” (Quoted in Hadden, Common History Common Struggle, p210)

In a certain sense, the narrow, Stalinist conception of the Civil Rights movement confirmed the idea of Paisley, Gregory Campbell and co. that civil rights were about Catholics versus Protestants. According to the Stalinists, the movement had to unite behind itself all “progressive” forces. This meant a policy of class collaboration, of uniting Catholic workers with the “progressive”, Catholic bosses. Whatever the intentions of the Civil Rights leaders this meant converting the movement effectively into a Catholic rather than a working-class front. In the words of McCann, “anti-unionist unity was, to this mind, the single most pernicious idea current in the North.”

RUC violence

After a period of agitation around housing, the first Civil Rights march in Derry took place on 5 October 1968. Using the pretext that the sectarian Apprentice Boys intended to march on the same day, the Stormont Home Secretary, William Craig, decided two days in advance to ban the march. The NICRA were in favour of calling off the march. It was only because the left-wing Housing Action Committee decided to defy the ban, that the NICRA reluctantly decided to put itself at its head.

The banned march was not large. Only a few hundred turned out. But the RUC reacted with ferocious violence. While speeches were being given before the march began, the RUC moved in from the front and the rear. Heavy reinforcements and water cannon had been brought into Derry. Before the marchers could set off, baton charges and water cannon were unleashed against the peaceful assembly. Heads and arms were smashed by the police, who chased marchers into the majority-Catholic Bogside. The Bogside exploded with outrage.

Suddenly jolted into seeing the significance of these events, the local middle classes – businessmen, clergymen and nationalist politicians – who had played no role in the movement, organised themselves into the Derry Citizens’ Action Committee (DCAC). In the name of “peace” and “unity”, huge pressure was exerted on the original organisers to accept them as the movement’s leadership. Only a few resisted.

A few days later, following a march by thousands of students from Queens University in Belfast, which was again blocked by Paisleyite thugs, the students organised themselves into People’s Democracy. As its name implies, the organisation’s principles were diffuse and not clearly worked out, but it leaned firmly to the left. They drew inspiration directly from the actions of the revolutionary students of the Sorbonne in Paris.

But wherever they went, Civil Rights marches were being met by the Frankenstein’s monster of loyalist sectarianism. This violent monster, a product of British imperialism, had now grown out of the control of its master. Their violence in turn was now a whip, accelerating the development of revolutionary consciousness.

Faced with a social explosion, O’Neill finally began to roll out more than merely verbal reforms. Craig was fired, the Derry Corporation was abolished, and the repressive “Special Powers Act” was repealed. As usual, it was the threat of revolution that finally prompted reform from above. However, the reforms fell far short of what the NICRA was demanding. At this stage, far from satisfying the militant workers and youth at the forefront of the movement, reforms only emboldened them further. Indeed on 16 November, a new march through Derry overwhelmed the police as 20,000 marched from the Bogside to the city centre.

Nevertheless, in the face of these paltry reforms, the NICRA and DCAC called for a complete cessation of marches. To these middle-class and Stalinist leaders, the methods of the angry, unemployed youths of Derry were “hooliganism”. Even in the face of the most brutal reactionary violence, in their view the masses should remain impassive. In the words of John Hume from the DCAC, “We must be non-violent to the point of being crushed into the ground. Violence gets publicity and if we create it [it] is bad publicity. If it is created against us it is good publicity.” (Irish News, 22 February 1969)

Leadership

Going into 1969, the atmosphere was tense. The Paisleyites were increasing their agitation about “betrayal” by O’Neill, while the official leaders acted to restrain the Civil Rights movement. The Stalinist NICRA “lefts” offered no alternative.

What was missing in Ireland in 1968-69 was a genuine revolutionary organisation. Such an organisation, refusing to bow to the pressure to mix banners with the middle-class leaders (whose moderation and nationalism repelled the Protestant workers) could have held aloft a clear socialist banner. On the basis of such a programme that linked the question of civil rights to the conditions of all workers – including Protestant workers in the North and workers in the South – a revolutionary opportunity could have opened up across Ireland.

But whilst a more radical left existed around People’s Democracy and Derry Labour Party, which was moving in a revolutionary direction, these organisations were diffuse and did not have a clear alternative programme or perspective. Instead, their radicalism was expressed in a greater willingness to mobilise on the streets, and greater bravery in confronting the sectarian regime.

It was under these circumstances on 1 January 1969, that radical students from People’s Democracy took the initiative to hold a new march from Belfast to Derry, defying the calls of the middle-class leaders for restraint. The march was gruelling. Hundreds of Paisleyite thugs constantly harassed the marchers, pelting them with bricks, bottles and stones. At Burntollet Bridge the march was set upon by loyalist thugs, who were joined by dozens of off-duty RUC men. They were brutally beaten with sticks, nailed clubs and bicycle chains.

Many marchers were hospitalised. Only a few bloodied and battered marchers arrived in Derry. They were met by thousands of outraged workers and youth. The RUC once more attacked the assembly, and pushed through into the Catholic Bogside, kicking in doors and smashing windows. Now the Bogside fought back. Vigilante committees were formed and barricades were thrown up to prevent the RUC from entering. On a gable at the edge of the Bogside the words, “You are now entering Free Derry,” were painted, and “Free Derry Radio” was established by residents.

In April, when new clashes with the police broke out, the residents of the Bogside were no longer prepared to accept the RUC batons without reply. This time it was the police who took a battering as the whole community organised to drive them back: 209 police officers suffering injuries as against 79 civilians.

At the summer of 1969, the North of Ireland stood on the brink of a social explosion. Provocations by loyalist sectarians, backed up by the RUC, had created a revolutionary mood in working-class, Catholic communities. The revolutionary youth who were at the forefront of the fighting were open to socialist ideas. The whole Orange state was the enemy and the ideas of Republicanism were also gaining ground. Meanwhile, in the eyes of the Unionist establishment, O’Neill’s reforms had completely failed to quell the discontent. Rather the wave of unrest continued its ascending curve. O’Neill was forced out in April but his replacement, Chichester “ChiChi” Clark, had no alternative policy.

Derry explodes

The spark which lit the powder keg came during the “marching season” of 1969. Every summer, groups like the Orange Order and the Apprentice Boys in Derry marched in commemoration of the victories scored by the armies of William of Orange in his fight against James II for the succession of the British throne in the 17th Century.

According to the myth, the victory of the “Williamites” over the “Jacobites” was a victory of Protestant free-thinking over the authoritarianism of the Catholic Church. In reality, however, William of Orange had the full support of the Catholic Church. In the Vatican, a Te Deum was even held in celebration of William’s victory at the Battle of the Boyne.

The Irish poor – Catholics and Protestants alike – had no interest in the victory of either party. But despite being pure mythology the victories of “King Billy” were – and still are – celebrated every year. These marches in reality were designed to impress on the Catholics their inferior position.

On 12 August 1969, the Apprentice Boys of Derry were marched along their route, taking them along the city walls and directly past the Bogside. Trouble started with the throwing of coins by Protestant youths at Catholics below. A riot quickly ensued and the RUC were thrown into action, attempting to penetrate the Bogside.

Derry exploded. The entire community threw themselves into organising self-defence. Already on the night of 11 August, a Defence Committee was established with the participation of Marxists from the Derry Labour Party, and here and there barricades had been thrown up in anticipation.

Now the entire working-class population threw themselves into repelling the RUC. Some assisted in helping the wounded, others helped supply petrol bombs, others prepared sandwiches to feed the fighters and ordinary people opened up their homes for use in the struggle. The whole area was closed off behind barricades. From the top of the High Flats on Rossville Street youths took up a prime position for bombarding the RUC from on high. And in order to take the pressure off the residents of the Bogside, the call was made for other areas to rise up in sympathy in order to stretch the RUC to the limit.

‘Have we guns?’

In Belfast and elsewhere rioting began in working class Catholic communities in direct response to the call from Derry. Until this point, working-class, Catholic residents in Belfast had been hesitant to join the struggle. The Catholic population was a much smaller proportion of the population and the fear was that unrest would be used by the Paisleyites to whip up a pogrom. But now RUC stations in Belfast were attacked. In the disorder, shots were fired. In response the RUC sent armoured cars with heavy machine-guns into Catholic areas. As they encroached, the residents were clearly not matched to meet the threat. Bravely, youths responded with stones and petrol bombs. When machine-gun fire was unleashed a nine-year-old boy was killed as he slept in his bed.

As the RUC encroached on the Catholic areas, they were followed by loyalist mobs who burnt out Catholic homes. As Catholics were burnt out of their homes and fled in their thousands, Ian Paisley claimed that they only burned because Catholic homes and churches were filled with petrol bombs and IRA ammunition. The press and Westminster politicians echoed the claims that behind the unrest was an IRA conspiracy. The aim was to stampede the Protestants into the arms of reaction. The real possibility was forming of a devastating pogrom and a slide into all-out civil war.

Events were starting to take a similarly ominous turn in Derry. For three days the working-class residents of Derry’s Bogside successfully fought the RUC and kept them out of their community. With the RUC exhausted and beaten, the government at Stormont were preparing to unleash the B Specials. Eamonn McCann, the left-wing leader of Derry Labour Party, described the moment the Derry residents were gripped by the realisation that they were facing, unarmed, the prospect of a pogrom:

“…looking through the haze of gas, past the police lines, we saw the Specials moving into Waterloo Place. They were about to be thrown into the battle. Undoubtedly they would use guns. The possibility that there was going to be a massacre struck hundreds of people simultaneously. ‘Have we guns?’ people shouted to one another, hoping that someone would know…”

But there were no guns. Contrary to the official government and press line, which detected the shadowy influence of the IRA at all moments of unrest in 1968-69, the IRA were an irrelevance until the early 1970s. Indeed they were seen as an anachronism by most.

In the 1950s the IRA had launched its “Border Campaign” – a guerrilla campaign aimed at uniting Ireland. The methods of guerrilla struggle – suitable for a peasant country – were doomed in advance to failure. The IRA’s forces in the North were so small that the failed campaign was launched almost entirely from the South.

The failure of their ineffectual campaign forced the majority of the IRA leadership to reassess their methods. Under Cathal Goulding in the 1960s, they made a sharp left turn. Whilst a new emphasis on class struggle was a positive step, the organisation failed to turn towards the traditions of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Connolly. Instead, they came under the influence of the Stalinist Communist Party of Great Britain.

Correctly, the new leadership rejected the traditional abstentionist policy of Republicanism. But instead of seeing the use of parliamentarism as a revolutionary tactic – as a tribune from which to agitate for socialist revolution – it was conceived in a reformist and pacifist way. The Irish revolution was divided into two “stages”. Instead of a revolutionary struggle of the working class whose final aim would be the overthrow of Stormont in the North and the bourgeois state in the South, and the establishment of a 32-county Socialist Republic, the IRA sought democratic reform and an end to discrimination. Parliamentary reform would come first, clearing the decks for united class action of the Catholic and Protestant workers. Only then would the basis for a struggle for socialist revolution be laid.

This two-stage reformist perspective, which precluded revolution or civil war, left the IRA leadership completely unprepared for the explosive events which unfolded in August 1969. Whilst rank and file IRA members participated in the fighting and were active on the Defence Committees, the organisation was woefully underprepared for a serious struggle. According to one IRA officer, they had only 60 men in Belfast in 1969, only half of whom were active. Their arsenal consisted of a few outdated WWII handguns and rifles left over from the Border Campaign. The leadership did little to acquire new arms in advance of the events of 1969.

Apparently, “IRA = I Ran Away” appeared on walls in Belfast. Whether true or merely apocryphal, it certainly corresponded to the feeling of many working-class, Catholic youths at the time. The failure of the leaders of the “Official” Republican movement to prepare adequately for self-defence led to disillusionment among rank and file IRA members with the leadership. It was an important element in aiding the rapid growth of the right-wing Provisionals following a split in the movement in late 1969 and early 1970.

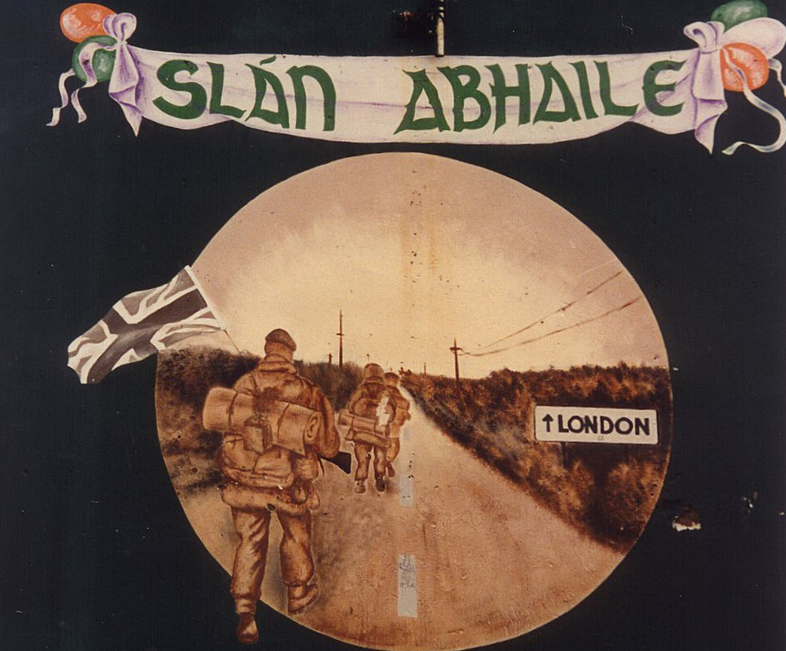

British troops sent in

On the third day of rioting, the Wilson government sent in the troops. Eamonn McCann captures the mood in Derry as troops positioned themselves at the edge of the Bogside:

“The Specials disappeared, the police pulled out quite suddenly and the troops, armed with submachine-guns, stood in a line across the mouth of William Street. Their appearance was clear proof that we had won the battle, that the RUC was beaten. That was welcomed. But there was confusion as to what the proper attitude to the soldiers might be.”

The troops had arrived and “Operation Banner” had begun. The sudden arrival of the troops was greeted with enthusiasm by the majority of Catholic workers and youth. They had beaten back the RUC. As for the troops, it was believed they had arrived to keep the peace. As McCann attests, this mood affected even the most class-conscious militants.

The troops had arrived, apparently to protect Catholics. Was this not to be welcomed? But how did this square with the opposition of socialists and Republicans to British imperialism?

In the absence of a trained, revolutionary organisation, even many of the best, radicalised workers and youth succumbed to this mood and welcomed the British troops.

It wasn’t just McCann who supported the arrival of the troops. The Civil Rights leaders also welcomed them. In Britain, many of the so-called Marxist sects like the SWP and most Labour lefts welcomed the sending of troops into the North. Ironically they would turn 180 degrees in a few years, and cheer on the insane campaign of the IRA. Only Militant stood apart. Despite howls of protest from the rest of the left, Militant warned that “the call made for the entry of British troops will turn to vinegar in the mouths of some of the Civil Rights leaders.”

In fact, the troops had not been sent in to protect the Catholics, but had been sent first and foremost to protect the interests of British imperialism. The British ruling class had their own reasons to be alarmed at the rapid descent of Northern Ireland towards civil war.

The real possibility of civil war and ethnic cleansing loomed large. Such a scenario would destabilise the regime in the South. Fighting would quickly spread to the British mainland, beginning in cities with large Irish populations like Liverpool and Glasgow. The economic impact would be devastating.

But perhaps more than anything, the British and the Irish capitalist classes looked on with dismay at the situation developing behind the barricades. The state had lost control. Citizens’ Defence Committees had taken over the running of communities in which 150,000 of Northern Ireland’s residents had barricaded themselves. Besides coordinating the fighting, the committees were taking on more and more functions including controlling traffic and policing crime. In working-class Catholic neighbourhoods, a revolutionary situation had developed and dual power had become an established fact.

Worst of all, these committees contained a definite left-wing trend, with Marxist ideas having a real influence. With the help of workers drawn into the struggle, Derry Young Socialists succeeded in establishing a regular newspaper with a mass circulation on the Bogside, the Barricades Bulletin, and mass meetings of thousands were held. This was an intolerable situation for the British and Irish bourgeoisie.

The South

A wave of sympathy with the embattled Catholic neighbourhoods swept the working class in the South. They demanded that the Fianna Fail government do something. In outbursts of verbal Republicanism, Taoiseach Jack Lynch threatened to send troops to the border. In fact, he went no further than establishing a field hospital in Donegal.

The government in the South were obviously not about to physically confront the regime in the North. Just a few years earlier, Lynch had been cordially sitting down to business with O’Neill. His outbursts, which included a demand for UN peacekeepers to be sent in, were really meant to satisfy the mood at home. But they were also a coded message to the British: get the troops in and sort it out!

Alarmed at the uncontrolled situation, with left-wingers dominant in many Defence Committees, one section of the Southern bourgeoisie opted to try and tip the balance of forces against the left by channelling cash and guns to the right-wing elements. Using a fund established to help victims of the violence, two Fianna Fail ministers, Haughey and Blaney, helped to covertly smuggle weapons and guns to the North.

This money was handed directly to the right-wing, rabidly anti-Communist Republican wing who had long despised the “Reds” who led the Official movement. It was these elements, representing the bourgeois wing of Republicanism, that split away to form the Provisional IRA.

The Official leadership used this fact to absolve themselves of their share of responsibility for the rise of the Provos. Nevertheless, it remains a fact that the Southern bourgeoisie provided an important push in the direction of sectarian civil war, which they feared less than socialism.

In late 1969 and early 1970, a split between the two wings of the IRA became complete. In this split, the Provisional IRA was formed. At first this went on largely unnoticed by the majority of people. The first outward sign of the split was the appearance of pin-on Easter lilies at the 1970 Easter Uprising commemorations. They were preferred by the Provo “traditionalists” to the stick-on ones used by the Official IRA (who came thereafter to be known as the “Stickies”).

Despite occasional lip-service to the “socialist republic”, the Provos were the old traditional “physical force” Republicans, who had never been at ease with the left shift of the Official leadership. They represented a bourgeois, right-wing, rabidly anti-Communist trend in Republicanism.

As a trickle of youths joined the IRA, which “wing” of the Republican movement they joined was more often than not accidental. Certainly, the connections that the Provos had with a section of Irish-American and Southern businessmen meant they were favoured because of their material support. Still, the IRA remained small. But events were impressing on thousands of the most advanced workers and youth the need for armed self-defence.

Workers’ self-defence

There was a strong, anti-sectarian mood throughout the working class at this time, and a desire to prevent a descent into the kind of bloodshed and violence that the North had witnessed in the 1920s.

On 21 July 1920, Protestants at the Harland and Wolff shipyard, which employed thousands of workers, were incited to expel “disloyal” workers. In response, a large mob drove out Catholics from the shipyard under a hail of iron rivets. It should be noted socialists and trade unionists were driven out too. In reward for these displays of “loyalty”, the bosses responded with a general assault which drove down the living standards of all workers in the North.

In 1969 it was a different matter. The mostly Protestant workforce was determined to stand against the Paisleyite bigots who wanted to see a rerun of the 1920s. In a mass meeting of all 8,000 workers, a motion was overwhelmingly passed calling for an end to the violence:

“This mass meeting of shipyard workers calls on the people of Northern Ireland for the immediate restoration of peace throughout the community. We recognise that the continuation of the present civil disorder can end only in economic disaster. We appeal to all responsible people to join with us in giving a lead to break the cycle of mutual recrimination arising from day-to-day incidents.” (Bleakley, “Peace in Ulster”, 1972)

Across the North, the defence committees had a largely non-sectarian character. In many mixed areas, Catholic and Protestant workers formed joint defence patrols to block the efforts of troublemakers from either side of the sectarian divide. In Derry’s Bogside, the socialists on the Defence Committee continued to maintain contacts with advanced workers in the majority-Protestant Fountain neighbourhood.

Under these conditions, had the unions put forward the slogan for the formation of non-sectarian, workers’ self-defence committees – modelled on the Irish Citizens Army that had been established by the Transport Union under Connolly’s leadership in 1913 – it could well have received a very positive reception and put a stop to the descent into tit-for-tat sectarian violence.

But the leaders of the labour movement – of the trade unions (the NIC-ICTU) and the Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP) – completely, and quite literally, sold out. In response to the unrest, in September 1969 representatives of the trade union movement met with representatives of the Unionist government of Chichester Clark.

The result was a joint statement in which the government and the trade union leaders called for the barricades to be taken down: “the most valuable contribution that people can make at this time is to try to secure the removal of the barricades by peaceful and voluntary means in conjunction with the security forces.”

The trade union leaders had no other perspective than restoring “law and order”. For this act of utter treachery, they received their fifty pieces of silver in the form of an annual government grant of £10,000 (Hadden p273).

The role of the NILP was no less ignominious. Although at a rank and file level there was a shift to the left in places, such as in Derry where the Labour Party moved in the direction of Marxism, the leadership clung tightly to the methods of reformism. In the context of a sectarian state, reformist adaptation meant adaptation to Unionism. As a sectarian wedge was driven between workers in the North, this refusal to break with reformism meant certain death for the NILP.

With the threat of a pogrom looming large in August 1969, many of the left-wingers who had mobilised through the Derry Labour Party began to drift towards the Official IRA and began training in the use of arms over the border in Donegal. They were not about to meet the threat of a pogrom unarmed in the future.

Repression

The failure of the workers’ leaders to link armed, self-defence to the labour movement left a tremendous vacuum. For a short period, this was not obvious, because the army seemed to be a buffer.

In September, a joint effort by bishops and middle-class, “moderate” nationalist leaders succeeded in talking the masses into bringing the barricades down. In October, the RUC were disarmed and the B Specials were abolished. It seemed as though the British had intervened on the side of the Catholics after all.

But in reality, the B Specials had just been replaced by the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR). Many former B Specials joined en masse. At times, 10-20% of UDR members would also be part of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), the biggest paramilitary group that operated during the Troubles. The UDR became a ready source of weapons for loyalist paramilitaries.

The real character of the British occupation soon made itself felt. On 26 June 1970, an unrepentant Bernadette Devlin lost her appeal against a conviction for her part in the defence of the Bogside in August 1969. The outraged residents of the Bogside once more erupted in anger, this time clashing with the army.

The following day, an attempt was made by the Orange Order to march on the Catholic enclave of the Short Strand in East Belfast. The sectarian provocation escalated from stone throwing to the throwing of petrol bombs at St Michael’s Church. The Provisional IRA responded with gunfire and in the gun battle that ensued (dubbed the “Battle of St Matthews”) successfully kept the loyalists from encroaching. For the first time, the Provos came forward as defenders of Catholic workers. The Unionists were up in arms that the British army had failed to intervene.

The British troops now showed the meaning of their presence. Far from being stationed to protect the Catholics, they had really been deployed to establish stability in the interests of British imperialism. This meant first and foremost restoring order and restoring the authority of the state. Whilst the barricades had come down, there remained “no-go” areas for the state, unrest continued, civil rights agitation had not ended, and armed members of both wings of the IRA were continuing to operate.

With brute force, the British hoped to break the back of the unrest, disarm the IRA and placate the Unionists. On such a basis they imagined they might draw an end to “Operation Banner”. The policy was an unmitigated disaster.

A few days after the “Battle of St Matthews”, the British army declared a curfew in the Catholic, working-class, Falls Road area in Belfast. Going from house to house, they were determined to smoke out the IRA. With the utmost brutality, they ransacked hundreds of Catholic homes. When indignant, local women began fighting back, the army responded by filling the neighbourhood with choking CS gas. In “searches” conducted by the British army, houses were completely torn up, 337 people were arrested, 78 were wounded and 4 were killed.

The Provos

Far from cowing the Catholic population or immobilising the Provos as they had hoped, the repression turned the mood of the Catholic working class of Belfast to rage. The youth looked en masse to anyone who would give them guns. The Official Republican leaders, the Civil Rights leaders and the labour movement leaders had all been caught off guard by the development of events, and when the question of arms posed itself, none had any answers.

The Provos however had a simple answer. In the words of Billy McKee, an IRA commander in Belfast, “This is our opportunity with the Brits on the streets. It’s what we want, an open confrontation with the Brits. Get the Brits out through armed resistance.”

They believed that the British were the principal enemy and the national division of Ireland was the main cause of all the problems suffered by the Catholic workers. The physical presence of the British posed this point blank and they seriously believed that through direct armed conflict they could drive the British out, thus uniting Ireland by brute force. The British army presence was a gift.

The Provos had no compunctions about handing out weapons to any young person looking to defend themselves and their community. A direct military confrontation was just what they wanted. And after events such as the Falls Curfew, a deluge of young people joined the Provos in Belfast.

In the absence of armed self-defence, the Provos were turned into a serious force with mass support in working-class, Catholic neighbourhoods almost overnight. McCann described them as “the inrush which filled the vacuum left by the absence of a socialist option.” The Provos completely detached the national question from social and class questions. By purely military means, they believed that a brave, armed minority could defeat the might of British imperialism.

Against one of the most powerful military machines in the world, the Provo campaign was a disastrous adventure. They immediately came up against the fact that one million Protestants were opposed to the unification of Ireland. So long as that meant unification on a capitalist basis with the backward and Catholic Church-dominated South, that mood would never soften.

Instead of combining self-defence with a class appeal to the Protestant workers, explaining the meaning of a Socialist Republic, the Provos set out to achieve their ends militarily, against the will of Protestant workers! The working-class Catholic youth who joined the IRA were not, in their overwhelming majority, against Protestants. And for the most part, the campaign of the IRA was not consciously sectarian.

But bombings targeting the army or infrastructure inevitably killed civilians. Accidents occurred and warning calls were mistimed. Reprisals for sectarian killings by the likes of the Shankill Butchers, themselves took on a sectarian, tit-for-tat character. The PIRA’s “armed struggle” (in reality individual terror) drove a deep wedge into the working class.

A wedge into the working class

Once the Provo campaign began in earnest, joint Catholic-Protestant vigilance groups ceased. In his book, McCann recalled how all contact between socialists in Derry’s Bogside and advanced workers in the Fountain ceased. Layers of Protestant workers were pushed into the hands of the British state. And it was not just Protestants in Northern Ireland. As the IRA campaign hit the British mainland with bombings in Birmingham and elsewhere, they provided a gift to the Tory press, who used it to whip up an anti-Irish mood.

The British for their part could not leave. They had no choice but to remain and try to either defeat the IRA as long as there was little chance of negotiation. The alternative would have been to pull out and watch the region spiral into civil war. But defeating the IRA was impossible. Each act of repression drove thousands of new recruits into their arms.

On 8 July 1971, the British army shot two young men in Derry, Seamus Cusack and Desmond Beattie. In his book, McCann relates how the next day, the Provos held their first mass rally in the town.

When internment without trial was introduced in 1971 – i.e. the mass arrest of Catholics without evidence by the British state – it only led to new unrest. A rent strike was called. Riots erupted. There were new mass arrests and a new flood of angry, young recruits into the Provisionals.

And on 30 Jan 1972, the final break took place. The paratroop regiment met a peaceful and unarmed march in Derry with live ammunition. 14 people were killed. The aim had been to smash the movement off the streets, and to re-establish “order”. Certainly what remained of any illusion that it was possible to achieve change through peaceful street protest was finally smashed once and for all on “Bloody Sunday”.

Stalemate

The “armed struggle” took on an infernal logic of its own. Its effects were entirely reactionary. The IRA campaign was used by the ruling class to beef up its apparatus of repression. Each act of repression by the British state drew an inexhaustible reserve of young, Catholic recruits into the IRA. The inevitable outcome was a stalemate. And yet it took two and a half decades of bloodshed; of 3,000 lives lost, including hundreds of brave, young Catholics who really felt they were fighting for a 32-county socialist Republic; before this fact was squarely recognised.

But the Provisionals didn’t turn away from these bankrupt methods towards the revolutionary, socialist Republicanism, represented by the likes of James Connolly. Instead, they turned towards the bankrupt methods of reformism. In 1994 the IRA issued a ceasefire and in 1998 they signed the Good Friday Agreement (GFA). Although they dare not admit it, the GFA (which was a rehash of the 1973 Sunningdale Agreement) represented an admission of defeat and a betrayal of the struggle for a united Ireland.

What had two and a half decades of “armed struggle” achieved? The sectarian divide in the working class was widened into a gaping chasm. The wider this divide has grown, the further the prospect of a united Ireland has receded. However “radical” the guerrilla methods of the Provisionals seemed, in content their politics were those of a bourgeois, right-wing trend in Republicanism.

Since the signing of the GFA, this has become abundantly clear as the former guerrillas have converted themselves into bourgeois politicians, governing for ten years with Ian Paisley’s DUP. Together they were in complete agreement on the need for anti-working class policies in the North.

But as in the period since partition, history has not stood still. The methods of individual terror and guerrillaism have exhausted themselves. The paramilitary groups that remain active in Northern Ireland today – “loyalist” or “republican” – are despised by, and isolated from the working class. Without mass support, disconnected from the working class, groups like the so-called “New IRA” have degenerated into lumpenism, criminality and drug dealing.

For two decades reformist ideas have also been tested at Stormont, and have failed in the context of a deepening crisis of capitalism. This is what lies at the root of the collapse of Stormont in 2017.

But most importantly of all, the only force capable of uniting Ireland, on a socialist basis – the working class – has been immeasurably strengthened in Ireland, North and South. Meanwhile the sectarian organisations – the Orange Order and the Catholic Church – have seen a collapse in their authority.

The bankruptcy of capitalism in the North of Ireland has seen an increasing bankruptcy of Unionism, which has lost its historic majority for the first time in history. Today far fewer young people identify as nationalist or unionist. A new generation has grown up, which is looking for an alternative, which is really looking for a path to socialist revolution.

The task is to return to the revolutionary, Marxist traditions of James Connolly and to build a mass working-class revolutionary party in Ireland, without illusions in reformism, pacifism or guerrillaism. Such a party, encompassing the most advanced layers of the Irish working class, could lead the workers of Ireland in sweeping away capitalism and establishing a Workers’ Republic. In doing so, it would reach out to the workers of Britain and elsewhere, laying the basis for a Socialist Europe and a World Federation of Socialist States. Only then, would the problems of Ireland be resolved.